In a first-of-its-kind decision, a federal court recently upheld the right of employees to sue their employer for allegedly cutting employee hours to less than 30 hours per week to avoid offering health insurance under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Specifically, the District Court for the Southern District of New York denied a defense Motion to Dismiss in a case where a group of workers allege that Dave & Buster’s (a national restaurant and entertainment chain) “right-sized” its workforce for the purpose of avoiding healthcare costs.

Although this case is in the very early stages of litigation and is far from being decided, you should monitor this for developments to determine whether you need to take action to deter potential copycat lawsuits.

One of the initial concerns by ACA critics is that many employers would respond to the Employer Mandate by reducing full-time employee hours to avoid the coverage obligation and associated penalties, increasing the number of part-time workers in the national economy. This is because the ACA does not require an employer to offer affordable, minimum-value coverage to employees generally working less than 30 hours per week.

Although the initial economic data analyzing the national workforce suggests that the predictions of wide-scale reduction in employee hours have not materialized, some employers have increased their reliance on part-time employees as an ACA strategy to manage the costs of the Employer Mandate.

Section 510 of ERISA prohibits discrimination and retaliation against plan participants and beneficiaries with respect to their rights to benefits. More specifically, ERISA Section 510 prohibits employers from interfering “with the attainment of any right to which such participant may become entitled under the plan.” Because many employment decisions affect the right to present or future benefits, courts generally require that plaintiffs show specific employer intent to interfere with benefits if they want to successfully assert a cause of action under ERISA Section 510.

The court found that the class of plaintiffs showed sufficient evidence in support of their claim that their participation in the health insurance plan was discontinued because the employer acted with “unlawful purpose” in realigning its workforce to avoid ACA-related costs. In this regard, the employees claimed that the company held meetings during which managers explained that the ACA would cost millions of dollars, and that employee hours were being reduced to avoid that cost.

However, if you are considering reducing your employee hours, you should carefully consider how such reductions are communicated to your workforce. Employers often have varied reasons for reducing employee hours, and many of those reasons have legitimate business purposes. It is vital that any communications made to your employees about such reductions describe the underlying rationale with clarity.

Beginning in Spring 2016, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Exchanges/Marketplaces will begin to send notices to employers whose employees have received government-subsidized health insurance through the Exchanges. The ACA created the “Employer Notice Program” to give employers the opportunity to contest a potential penalty for employees receiving subsidized health insurance via an Exchange.

The notices will identify any employees who received an advance premium tax credit (APTC). If a full-time employee of an applicable large employer (ALE) receives a premium tax credit for coverage through the Exchanges in 2016, the ALE will be liable for the employer shared responsibility payment. The penalty if an employer doesn’t offer full-time equivalent employees (FTEs) affordable minimum value essential coverage is $2,160 per FTE (minus the first 30) in 2016. If an employer offers coverage, but it is not considered affordable, the penalty is the lesser of $3,240 per subsidized FTE in 2016 or the above penalty. Penalties for future years will be indexed for inflation and posted on the IRS website. The Employer Notice Program does provide an opportunity for an ALE to file an appeal if employees claimed subsidies they were not entitled to.

The first batch of notices will be sent in Spring 2016 and additional notices will be sent throughout the year. For 2016, the notices are expected to be sent to employers if the employee received an APTC for at least one month in 2016 and the employee provided the Exchange with the complete employer address.

Last September, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued FAQs regarding the Employer Notice Program. The FAQs respond to several questions regarding how employers should respond if they receive a notice that an employee received premium tax credits and cost sharing reductions through the ACA’s Exchanges.

Employers will have an opportunity to appeal the employer notice by proving they offered the employee access to affordable minimum value employer-sponsored coverage, therefore making the employee ineligible for APTC. An employer has 90 days from the date of the notice to appeal. If the employer’s appeal is successful, the Exchange will send a notice to the employee suggesting the employee update their Exchange application to reflect that he or she has access or is enrolled in other coverage. The notice to the employee will further explain that failure to provide an update to their application may result in a tax liability.

An employer appeal request form is available on the Healthcare.gov website. For more details about the Employer Notice Program or the employer appeal request form visit www.healthcare.gov.

Although CMS has provided these guidelines to apply only to the Federal Exchange, it is likely that the state-based Exchanges will have similar notification programs.

Employers should prepare in advance by developing a process for handling the Exchange notices, including appealing any incorrect information that an employee may have provided to the Exchange. Advance preparation will enable you to respond to the notice promptly and help to avoid potential employer penalties.

You did it! Your 1095 forms are ready and going out to employees. Now what?

You guessed it: Employee confusion. You’re going to get some questions. If you’re the one in charge of providing the answers, remember a great offense is the best defense. You’ll want to answer the most common questions before they’re even asked.

We’ve put together a list of some basic things

employees will want to know, along with sample answers. Tailor these Q&As as

needed for your organization. and then send them out to employees using every channel you can (mail, e-mail, employee meetings, company

website, social media, posters). Tell employees how to get more detailed

information if they need it.

1. What is this form I’m receiving?

A 1095 form is a little bit like a W-2 form.

Your employer (and/or insurer) sends one copy to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS)

and one copy to you. A W-2 form reports your annual earnings. A 1095 form

reports your health care coverage throughout the year.

2. Who is sending it to me, when, and how?

Your employer and/or health insurance company should

send one to you either by mail or in person. They may send the form to you

electronically if you gave them permission to do so. You should receive it by

March 31, 2016. (Starting in 2017, you should receive it each year by January

31, just like your W-2.)

3. Why are you sending it to me?

The 1095 forms will show that you and your

family members either did or did not have health coverage with our organization during each month of

the past year. Because of the Affordable Care Act, every person must obtain

health insurance or pay a penalty to the IRS.

4. What am I supposed to do with this form?

Keep it for your tax records. You don’t actually

need this form in order to file your taxes, but when you do file, you’ll have to tell the IRS whether or not

you had health insurance for each month of 2015. The Form 1095-B or 1095-C

shows if you had health insurance through your employer. Since you don’t

actually need this form to file your taxes, you don’t have to wait to receive

it if you already know what months you did or didn’t have health insurance in

2015. When you do get the form, keep it with your other 2015 tax information in

case you should need it in the future to help prove you had health insurance.

5. What if I get more than one 1095 form?

Someone who had health insurance through more

than one employer during the year may receive a 1095-B or 1095-C from each

employer. Some employees may receive a Form 1095-A and/or 1095-B reporting

specific health coverage details. Just keep these—you do not need to send them

in with your 2015 taxes.

6. What if I did not get a Form 1095-B or a 1095-C?

If you believe you should have received one but

did not, contact the Benefits Department by phone or e-mail at this number or

address.

7. I have more questions—who do I contact?

Please contact _____ at ____. You can also go to

our (company) website and find more detailed questions and answers. An IRS website called

Questions and Answers about Health Care Information Forms for

Individuals (Forms 1095-A, 1095-B, and 1095-C)

covers most of what you need to know.

Congress and the IRS were busy changing laws governing employee benefit plans and issuing new guidance under the ACA in late 2015. Some of the results of that year-end governmental activity include the following:

The PATH Act, enacted by Congress and signed into law on December 18, 2015, made some the following changes to federal statutory laws governing employee benefit plans:

On December 16, 2015, the IRS issued Notice 2015-87, providing guidance on employee accident and health plans and employer shared-responsibility obligations under the ACA. Guidance provided under Notice 2015-87 applies to plan years that begin after the Notice’s publication date (December 16th), but employers may rely upon the guidance provided by the Notice for periods prior to that date.

Notice 2015-87 covers a wide-range of topics from employer reporting obligations under the ACA to the application of Health Savings Account rules to rules for identifying individuals who are eligible for benefits under plans administered by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Following are some of the highlights from Notice 2015-87, with a focus on provisions that are most likely to impact non-governmental employers.

The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) fee was established under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to advance comparative clinical effectiveness research. The PCORI fee is assessed on issuers of health insurance policies and sponsors of self-insured health plans. The fees are calculated using the average number of lives covered under the policy or plan, and the applicable dollar amount for that policy or plan year. The past PCORI fees were—

The new adjusted PCORI fee is—

Employers and insurers will need to file Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Form 720 and pay the updated PCORI fee by July 31, 2016

Transitional Reinsurance Fee

Like the PCORI fee, the transitional reinsurance fee was established under the ACA. It was designed to reinsure the marketplace exchanges. Contributing entities are required to make contributions towards these reinsurance payments. A “contributing entity” is defined as an insurer or third-party administrator on behalf of a self-insured group health plan. The past transitional reinsurance fees were

The new adjusted transition reinsurance fee is—

On October 7, 2015 President Obama signed the Protecting Affordable Coverage for Employees (PACE) Act that amends the Affordable Care Act (ACA) definition of a “small employer” for the purpose of purchasing health insurance coverage.

Prior to the signing of this amendment and beginning January 1, 2016, every state was required to expand the definition of the small group market to include employers with up to 100 employees. Prior to January 1, 2016 states had the flexibility to maintain the definition of a small employer to those with up to 50 employees and most states continued to do so.

The PACE Act repeals the mandatory expansion of the small group market to employers with up to 100 employees and reverts to the prior definition of up to 50 employees, although the states maintain flexibility to define the small market as up to 100 employees if they wish.

Under the ACA, health insurance offered in the small group market must meet strict underwriting requirements and cover all essential health benefits- conditions that do not apply in the large group market. Concerns about steep price increases and loss of benefit design flexibility from many businesses with 51 – 100 employees who would be re-classified as a “small employer” prompted this bi-partisan amendment to the law.

What Happens Now?

Numerous questions surround the passage of this amendment to the ACA given the fact that the change has happened so late in 2015. Insurance carriers have already filed their small group 2016 plan rates assuming the expansion of this market space and many employers impacted by their re-classification have already secured coverage or are finalizing plans for 2016 coverage. Here are some questions that hopefully will be addressed in the near future:

Employers who are impacted by this ACA amendment should monitor the situation and determine what may be the best course of action for your employees.

In a 6-3 decision handed down June 25th by the U.S. Supreme Court, the IRS was authorized to issue regulations extending health insurance subsidies to coverage purchased through health insurance exchanges run by the federal government or a state (King v. Burwell, No. 14-114 ).

This means employers cannot avoid employer shared responsibility penalties under IRC section 4980H (“Code § 4980H”) with respect to an employee solely because the employee obtained subsidized exchange coverage in a state that has a health insurance exchange set up by the federal government instead of by the state. It also means that President Barack Obama’s 2010 health care reform law will not be unraveled by the Supreme Court’s decision in this case. The law’s requirements applicable to employers and group health plans continue to apply without change.

What Was the Case About?

IRC section 36B (“Code § 36B”), created by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (“ACA”), provides that an individual who buys health insurance “through an Exchange established by the State under section 1311 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act” (emphasis added) generally is entitled to subsidies unless the individual’s income is too high. Thus, the words of the statute conditioned one’s right to an exchange subsidy on one’s purchase of ACA coverage in a state run exchange.

Since 2014, an individual who fails to maintain health insurance for any month generally is subject to a tax penalty unless the individual can show that no affordable coverage was available. The law defines affordability for this purpose in such a way that, without a subsidy, health insurance would be unaffordable for most people.

The plaintiffs in King, residents of one of the 34 states that did not establish a state run health insurance exchange argued that if subsidies were not available to them, no health insurance coverage would be affordable for them and they would not be required to pay a penalty for failing to maintain health insurance. The IRS, however, made subsidized federal exchange coverage available to them similar to coverage in a state run exchange.

It is ACA § 1311 that established the funding and other incentives for “the States” to each establish a state-run exchange through which residents of the state could buy health insurance. Section 1311 also provides that the Secretary of the Treasury will appropriate funds to “make available to each State” and that the “State shall use amounts awarded for activities (including planning activities) related to establishing an American Health Benefit Exchange.” Section 1311 describes an “American Health Benefit Exchange” as follows:

Each State shall, not later than January 1, 2014, establish an American Health Benefit Exchange (referred to in this title as an “Exchange”) for the State that (A) facilitates the purchase of qualified health plans; (B) provides for the establishment of a Small Business Health Options Program and © meets [specific requirements enumerated].

An entirely separate section of the ACA provides for the establishment of a federally-run exchange for individuals to buy health insurance if they reside in a state that does not establish a 1311 exchange. That section – ACA § 1321 – withholds funding from a state that has failed to establish a 1311 exchange.

Notwithstanding the statutory language Congress used in the ACA (i.e., literally conditioning an individual’s eligibility subsidized exchange coverage on the purchase of health insurance through a state’s 1311 exchange), the Supreme Court determined that the language is ambiguous. Having found that the text is ambiguous, the Court stated that it must determine what Congress really meant by considering the language in context and with a view to the placement of the words in the overall statutory scheme.

When viewed in this context, the Court concluded that the plain language could not be what Congress actually meant, as such interpretation would destabilize the individual insurance market in those states with a federal exchange and likely create the “death spirals” the ACA was designed to avoid. The Court reasoned that Congress could not have intended to delegate to the IRS the authority to determine whether subsidies would be available only on state run exchanges because the issue is of such deep economic and political significance. The Court further noted that “had Congress wished to assign that question to an agency, it surely would have done so expressly” and “[i]t is especially unlikely that Congress would have delegated this decision to the IRS, which has no expertise in crafting health insurance policy of this sort.”

What Now?

Regardless of whether one agrees with the Supreme Court’s King decision, the decision prevents any practical purpose for further discussion about whether the IRS had authority to extend taxpayer subsidies to individuals who buy health insurance coverage on federal exchanges.

The ACA’s next major compliance requirements for employers: Employers with fifty or more fulltime and fulltime equivalent employees need to ensure that they are tracking hours of service and are otherwise prepared to meet the large employer reporting requirements for 2015 (due in early 2016) ). Employers of any size that sponsor self-funded group health plans need to ensure that they are prepared to meet the health plan reporting requirements for 2015 (also due in early 2016). All employers that sponsor group health plans also should be considering whether and to what extent the so-called Cadillac tax could apply beginning in 2018.

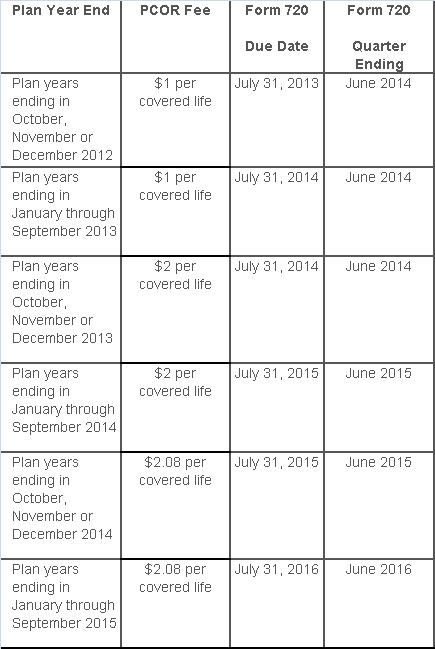

The Affordable Care Act added a patient-centered outcomes research (PCOR) fee on health plans to support clinical effectiveness research. The PCOR fee applies to plan years ending on or after Oct. 1, 2012, and before Oct. 1, 2019. The PCOR fee is due by July 31 of the calendar year following the close of the plan year. For plan years ending in 2014, the fee is due by July 31, 2015.

PCOR fees are required to be reported annually on Form 720, Quarterly Federal Excise Tax Return, for the second quarter of the calendar year. The due date of the return is July 31. Plan sponsors and insurers subject to PCOR fees but not other types of excise taxes should file Form 720 only for the second quarter, and no filings are needed for the other quarters. The PCOR fee can be paid electronically or mailed to the IRS with the Form 720 using a Form 720-V payment voucher for the second quarter. According to the IRS, the fee is tax-deductible as a business expense.

The PCOR fee is assessed based on the number of employees, spouses and dependents that are covered by the plan. The fee is $1 per covered life for plan years ending before Oct. 1, 2013, and $2 per covered life thereafter, subject to adjustment by the government. For plan years ending between Oct. 1, 2014, and Sept. 30, 2015, the fee is $2.08. The Form 720 instructions are expected to be updated soon to reflect this increased fee.

This chart summarizes the fee schedule based on the plan year end and shows the Form 720 due date. It also contains the quarter ending date that should be reported on the first page of the Form 720 (month and year only per IRS instructions). The plan year end date is not reported on the Form 720.

For insured plans, the insurance company is responsible for filing Form 720 and paying the PCOR fee. Therefore, employers with only fully- insured health plans have no filing requirement.

If an employer sponsors a self-insured health plan, the employer must file Form 720 and pay the PCOR fee. For self-insured plans with multiple employers, the named plan sponsor is generally required to file Form 720. A self-insured health plan is any plan providing accident or health coverage if any portion of such coverage is provided other than through an insurance policy.

Since the fee is a tax assessed against the plan sponsor and not the plan, most funded plans subject to ERISA must not pay the fee using plan assets since doing so would be considered a prohibited transaction by the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL). The DOL has provided some limited exceptions to this rule for plans with multiple employers if the plan sponsor exists solely for the purpose of sponsoring and administering the plan and has no source of funding independent of plan assets.

Plans sponsored by all types of employers, including tax-exempt organizations and governmental entities, are subject to the PCOR fee. Most health plans, including major medical plans, prescription drug plans and retiree-only plans, are subject to the PCOR fee, regardless of the number of plan participants. The special rules that apply to Health Reimbursement Accounts (HRAs) and Health Flexible Spending Accounts (FSAs) are discussed below.

Plans exempt from the fee include:

If a plan sponsor maintains more than one self-insured plan, the plans can be treated as a single plan if they have the same plan year. For example, if an employer has a self-insured medical plan and a separate self-insured prescription drug plan with the same plan year, each employee, spouse and dependent covered under both plans is only counted once for purposes of the PCOR fee.

The IRS has created a helpful chart showing how the PCOR fee applies to common types of health plans.

Health Reimbursement Accounts (HRAs) - Nearly all HRAs are subject to the PCOR fee because they do not meet the conditions for exemption. An HRA will be exempt from the PCOR fee if it provides benefits only for dental or vision expenses, or it meets the following three conditions:

Health Flexible Spending Accounts (FSAs) - A health FSA is exempt from the PCOR fee if it satisfies an availability condition and a maximum benefit condition.

Additional special rules for HRAs and FSAs . Once an employer determines that its HRA or FSA is subject to the PCOR fee, the employer should consider the following special rules:

The IRS provides different rules for determining the average number of covered lives (i.e., employees, spouses and dependents) under insured plans versus self-insured plans. The same method must be used consistently for the duration of any policy or plan year. However, the insurer or sponsor is not required to use the same method from one year to the next.

A plan sponsor of a self-insured plan may use any of the following three

methods to determine the number of covered lives for a plan year:

1. Actual count method. Count the covered lives on each day of the plan year and divide by the number of days in the plan year.

Example: An employer has 900 covered lives on Jan. 1, 901 on Jan. 2, 890 on

Jan. 3, etc., and the sum of the lives covered under the plan on each day of

the plan year is 328,500. The average number of covered lives is 900 (328,500 ÷

365 days).

2. Snapshot method. Count the covered lives on a single day in each quarter (or more than one day) and divide the total by the number of dates on which a count was made. The date or dates must be consistent for each quarter. For example, if the last day of the first quarter is chosen, then the last day of the second, third and fourth quarters should be used as well.

Example: An employer has 900 covered lives on Jan. 15, 910 on April 15, 890 on

July 15, and 880 on Oct. 15. The average number of covered lives is 895 [(900 +

910+ 890+ 880) ÷ 4 days].

As an alternative to counting actual lives, an employer can count the number of

employees with self-only coverage on the designated dates, plus the number of

employees with other than self-only coverage multiplied by 2.35.

3. Form 5500 method. If a Form 5500 for a plan is filed before the due date of the Form 720 for that year, the plan sponsor can determine the number of covered lives based on the Form 5500. If the plan offers just self-only coverage, the plan sponsor adds the participant counts at the beginning and end of the year (lines 5 and 6d on Form 5500) and divides by 2. If the plan also offers family or dependent coverage, the plan sponsor adds the participant counts at the beginning and end of the year (lines 5 and 6d on Form 5500) without dividing by 2.

Example: An employer offers single and family coverage with a plan year ending

on Dec. 31. The 2013 Form 5500 is filed on June 5, 2014, and reports 132

participants on line 5 and 148 participants on line 6d. The number of covered

lives is 280 (132 + 148).

To evaluate liability for PCOR fees, plan sponsors should identify all of their plans that provide medical benefits and determine if each plan is insured or self-insured. If any plan is self-insured, the plan sponsor should take the following actions:

According to recent news reports, nearly half of the 17 Exchanges run by states and the District of Columbia under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) are struggling financially:

Many of the online exchanges are wrestling with surging costs, especially for balky technology and expensive customer call centers — and tepid enrollment numbers. To ease the fiscal distress, officials are considering raising fees on insurers, sharing costs with other states and pressing state lawmakers for cash infusions. Some are weighing turning over part or all of their troubled marketplaces to the federal exchange, HealthCare.gov, which now works smoothly.

Of course, many states can’t solve their financial troubles easily. As independent entities, their income depends on fees imposed on insurers, which is then often passed on to the consumer signing up for health care. However, those fees are entirely contingent on how many people enroll in that particular Exchange; low enrollment invariably means higher costs.

Low enrollment is where the trouble thickens. The recently completed open enrollment period only rose 12 percent to 2.8 million sign-ups for state Exchanges, according to The Washington Post. Comparatively, the federal Exchange saw an increase of 61 percent to 8.8 million people.

According to the Post, state Exchanges have operating budgets between “$28 million and $32 million”. Most of the money tends to go to call centers, “Enrollment can be a lengthy process — and in several states, contractors are paid by the minute. An even bigger cost involves IT work to correct defective software that might, for example, make mistakes in calculating subsidies.”

However, The Fiscal Times contends that, “Some states may be misusing Obamacare grants in order to keep their state insurance exchanges operating—potentially flouting a provision in the law requiring them to cover the costs of the exchanges themselves starting this year.”

In fact, the ACA provided about $4.8 billion in grants to help states build and promote their Exchanges. As the article explains, before this year, states could use the grant money on overhead costs. However, a new provision that went into effect in January 2015 says that states can’t use the grants on maintenance and staffing costs; grant money must be spent on design, development and implementation costs.

The Fiscal Times spotlights California as a prime example of why state Exchanges are in troubled waters:

One of the worst examples comes from California, where the state’s exchange has been touted the most successful in the country for enrolling thousands of people. Covered California has already used up about $1.1 billion in federal funding to get its exchange up and running and is now expected to run a nearly $80 million deficit by the end of the year, according to the Orange County Register. The state has already set aside about $200 million to cover that, but the long-term sustainability of the program is very much in question.

In addition, state Exchanges like Hawaii might have to switch to the federal Exchange, Healthcare.gov, because of on-going financial solvency issues. “This is a contingency that is being imposed on any state-based exchange that doesn’t have a funded sustainability plan in play,” said Jeff Kissel, CEO of the Hawaii Health Connector.

According to the Post, states with the lowest enrollment are facing the biggest financial problems:

Turning operations over to the federal Exchange seems to be a popular alternative, but it doesn’t come without a cost: $10 million per Exchange, to be exact.

Although there are many options for state Exchanges to consider, it is likely that they will hold off on any final decisions until after the Supreme Court decides King v. Burwell. In this case, the Chief Justices will make a ruling in June that could either send a lifeline to ACA or remove a fundamental pillar of the law by under-cutting its ability to extend health insurance coverage to millions of Americans through its subsidy program.

The appellants in the King v. Burwell case say that IRS rule conflicts with the statutory language set forth in the ACA, which limits subsidy payments to individuals or families that enroll in the state-based Exchanges only. If the Court relies on a literal interpretation of the ACA’s language, millions of Americans who live in more than half of the states where the federal Exchange operates will not receive subsidies, thus undoing a fundamental pillar of the law. (Read more about the court case here.)

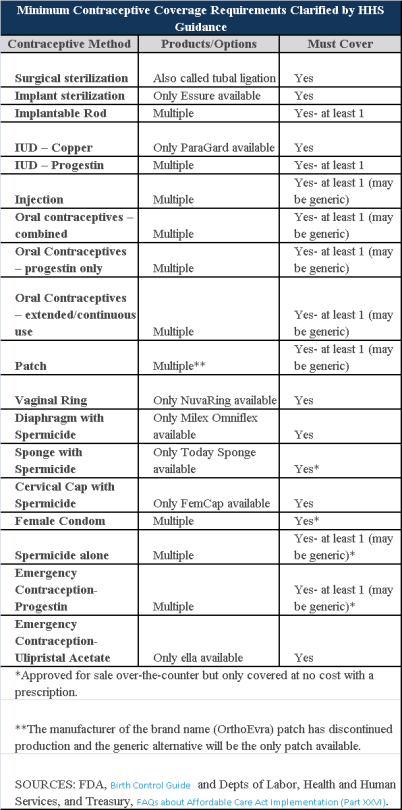

Plans and insurers must cover all 18 contraception methods approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, according to a new set of questions and answers on the Affordable Care Act’s preventive care coverage requirements.

“Reasonable medical management” still may be used to steer members to specific products within those methods of contraception. A plan or insurer may impose cost-sharing on non-preferred items within a given method, as long as at least one form of contraception in each method is covered without cost-sharing.

However, an individual’s physician must be allowed to override the plan’s drug management techniques if the physician finds it medically necessary to cover without cost-sharing an item that a given plan or insurer has classified as non-preferred, according to one of the frequently asked questions from the U.S. Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services and the Treasury.

The ACA mandated all plans and insurers to cover preventive care items, as defined by the Public Health Service Act, without cost-sharing. Eighteen forms of female contraception are included under the preventive care list. The individual FAQs on contraception clarified the following requirements.

The FAQ comes just weeks after reports and news coverage detailed health plan violations of the women coverage provisions of the ACA.

Testing and Dependent Care Answers

In questions separate from contraception, plans and insurers were told they must cover breast cancer susceptibility (BRCA-1 or BRCA-2) testing without cost-sharing. The test identifies whether the woman has genetic mutations that make her more susceptible to BRCA-related breast cancer.

Another question stated that if colonoscopies are performed as preventive screening without cost-sharing, then plans could not impose cost-sharing on the anesthesia component of that service.