In July 2015, President Obama signed into law the Trade Preferences Extension Act of 2015. Included in the bill was an important provision that affects welfare and retirement benefit plans. The Act sizably increases filing penalties for information return and statement failures under the Internal Revenue Code, effective for filings after December 31,2015. Employers now face significantly larger penalties for failing to correctly file and furnish the ACA forms 1094 and 1095 (shared responsibility reporting requirements) as well as Forms W-2 and 1099-R.

Background

Sections 6721 and 6722 of the IRC impose penalties associated with failures to file- or to file correct- information returns and statements. Section 6721 applies to the returns required to be filed with the IRS, and Section 6722 applies to statements required to be provided generally to employees.These penalty provisions apply to the ACA shared responsibility reporting Forms 1094-B, 1094-C, 1095-B, and 1095-C (Sections 6055 & 6056) failures as well as other information returns and statement failures, like those on Forms W-2 and 1099.

For ACA:

The Sections 6055 & 6056 reporting requirements are effective for medical coverage provided on or after January 1, 2015, with the first information returns to be filed with the IRS by February 29, 2016 (or March 31,2016 if filing electronically) and provided to individuals by February 1, 2016.

Increase in Penalties

The Trade Preferences Extension Act of 2015 (Act) contains several tax provisions in addition to the trade measures that were the focus of the bill. Provided as a revenue offset provision, the law significantly increases the penalty amounts under Sections 6721 and 6722. A failure includes failing to file or furnish information returns or statements by the due date, failing to provide all required information, as well as failing to provide correct information.

The law increases the penalty for:

Other penalty increase also apply, including those associated with timely filing a corrected return. Penalties could also provide a one-two punch under the ACA for employers and other responsible entities. For example, under Sec 6056, applicable large employers (ALE) must file information returns to the IRS (the 1094-B and 1094-C) as well as furnish statements to employees (the 1095-B and 1095-C). So incorrect information shared on those forms could result in a double penalty- one associated with the information return to the IRS and the other associated with individual statements to employees.

Final regulations on the ACA reporting requirements provide short-term relief from these penalties. For reports files in 2016 (for 2015 calendar year info), the IRS will not impose penalties on ALE members that can show they made a “good-faith effort” to comply with the information reporting requirements. Specifically, relief is provided for incorrect or incomplete info reported on the return or statement, including Social Security numbers, but not for failing to file timely.

In a 6-3 decision handed down June 25th by the U.S. Supreme Court, the IRS was authorized to issue regulations extending health insurance subsidies to coverage purchased through health insurance exchanges run by the federal government or a state (King v. Burwell, No. 14-114 ).

This means employers cannot avoid employer shared responsibility penalties under IRC section 4980H (“Code § 4980H”) with respect to an employee solely because the employee obtained subsidized exchange coverage in a state that has a health insurance exchange set up by the federal government instead of by the state. It also means that President Barack Obama’s 2010 health care reform law will not be unraveled by the Supreme Court’s decision in this case. The law’s requirements applicable to employers and group health plans continue to apply without change.

What Was the Case About?

IRC section 36B (“Code § 36B”), created by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (“ACA”), provides that an individual who buys health insurance “through an Exchange established by the State under section 1311 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act” (emphasis added) generally is entitled to subsidies unless the individual’s income is too high. Thus, the words of the statute conditioned one’s right to an exchange subsidy on one’s purchase of ACA coverage in a state run exchange.

Since 2014, an individual who fails to maintain health insurance for any month generally is subject to a tax penalty unless the individual can show that no affordable coverage was available. The law defines affordability for this purpose in such a way that, without a subsidy, health insurance would be unaffordable for most people.

The plaintiffs in King, residents of one of the 34 states that did not establish a state run health insurance exchange argued that if subsidies were not available to them, no health insurance coverage would be affordable for them and they would not be required to pay a penalty for failing to maintain health insurance. The IRS, however, made subsidized federal exchange coverage available to them similar to coverage in a state run exchange.

It is ACA § 1311 that established the funding and other incentives for “the States” to each establish a state-run exchange through which residents of the state could buy health insurance. Section 1311 also provides that the Secretary of the Treasury will appropriate funds to “make available to each State” and that the “State shall use amounts awarded for activities (including planning activities) related to establishing an American Health Benefit Exchange.” Section 1311 describes an “American Health Benefit Exchange” as follows:

Each State shall, not later than January 1, 2014, establish an American Health Benefit Exchange (referred to in this title as an “Exchange”) for the State that (A) facilitates the purchase of qualified health plans; (B) provides for the establishment of a Small Business Health Options Program and © meets [specific requirements enumerated].

An entirely separate section of the ACA provides for the establishment of a federally-run exchange for individuals to buy health insurance if they reside in a state that does not establish a 1311 exchange. That section – ACA § 1321 – withholds funding from a state that has failed to establish a 1311 exchange.

Notwithstanding the statutory language Congress used in the ACA (i.e., literally conditioning an individual’s eligibility subsidized exchange coverage on the purchase of health insurance through a state’s 1311 exchange), the Supreme Court determined that the language is ambiguous. Having found that the text is ambiguous, the Court stated that it must determine what Congress really meant by considering the language in context and with a view to the placement of the words in the overall statutory scheme.

When viewed in this context, the Court concluded that the plain language could not be what Congress actually meant, as such interpretation would destabilize the individual insurance market in those states with a federal exchange and likely create the “death spirals” the ACA was designed to avoid. The Court reasoned that Congress could not have intended to delegate to the IRS the authority to determine whether subsidies would be available only on state run exchanges because the issue is of such deep economic and political significance. The Court further noted that “had Congress wished to assign that question to an agency, it surely would have done so expressly” and “[i]t is especially unlikely that Congress would have delegated this decision to the IRS, which has no expertise in crafting health insurance policy of this sort.”

What Now?

Regardless of whether one agrees with the Supreme Court’s King decision, the decision prevents any practical purpose for further discussion about whether the IRS had authority to extend taxpayer subsidies to individuals who buy health insurance coverage on federal exchanges.

The ACA’s next major compliance requirements for employers: Employers with fifty or more fulltime and fulltime equivalent employees need to ensure that they are tracking hours of service and are otherwise prepared to meet the large employer reporting requirements for 2015 (due in early 2016) ). Employers of any size that sponsor self-funded group health plans need to ensure that they are prepared to meet the health plan reporting requirements for 2015 (also due in early 2016). All employers that sponsor group health plans also should be considering whether and to what extent the so-called Cadillac tax could apply beginning in 2018.

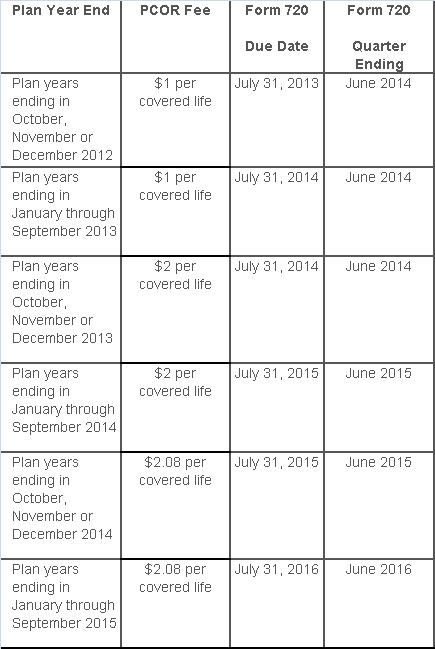

The Affordable Care Act added a patient-centered outcomes research (PCOR) fee on health plans to support clinical effectiveness research. The PCOR fee applies to plan years ending on or after Oct. 1, 2012, and before Oct. 1, 2019. The PCOR fee is due by July 31 of the calendar year following the close of the plan year. For plan years ending in 2014, the fee is due by July 31, 2015.

PCOR fees are required to be reported annually on Form 720, Quarterly Federal Excise Tax Return, for the second quarter of the calendar year. The due date of the return is July 31. Plan sponsors and insurers subject to PCOR fees but not other types of excise taxes should file Form 720 only for the second quarter, and no filings are needed for the other quarters. The PCOR fee can be paid electronically or mailed to the IRS with the Form 720 using a Form 720-V payment voucher for the second quarter. According to the IRS, the fee is tax-deductible as a business expense.

The PCOR fee is assessed based on the number of employees, spouses and dependents that are covered by the plan. The fee is $1 per covered life for plan years ending before Oct. 1, 2013, and $2 per covered life thereafter, subject to adjustment by the government. For plan years ending between Oct. 1, 2014, and Sept. 30, 2015, the fee is $2.08. The Form 720 instructions are expected to be updated soon to reflect this increased fee.

This chart summarizes the fee schedule based on the plan year end and shows the Form 720 due date. It also contains the quarter ending date that should be reported on the first page of the Form 720 (month and year only per IRS instructions). The plan year end date is not reported on the Form 720.

For insured plans, the insurance company is responsible for filing Form 720 and paying the PCOR fee. Therefore, employers with only fully- insured health plans have no filing requirement.

If an employer sponsors a self-insured health plan, the employer must file Form 720 and pay the PCOR fee. For self-insured plans with multiple employers, the named plan sponsor is generally required to file Form 720. A self-insured health plan is any plan providing accident or health coverage if any portion of such coverage is provided other than through an insurance policy.

Since the fee is a tax assessed against the plan sponsor and not the plan, most funded plans subject to ERISA must not pay the fee using plan assets since doing so would be considered a prohibited transaction by the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL). The DOL has provided some limited exceptions to this rule for plans with multiple employers if the plan sponsor exists solely for the purpose of sponsoring and administering the plan and has no source of funding independent of plan assets.

Plans sponsored by all types of employers, including tax-exempt organizations and governmental entities, are subject to the PCOR fee. Most health plans, including major medical plans, prescription drug plans and retiree-only plans, are subject to the PCOR fee, regardless of the number of plan participants. The special rules that apply to Health Reimbursement Accounts (HRAs) and Health Flexible Spending Accounts (FSAs) are discussed below.

Plans exempt from the fee include:

If a plan sponsor maintains more than one self-insured plan, the plans can be treated as a single plan if they have the same plan year. For example, if an employer has a self-insured medical plan and a separate self-insured prescription drug plan with the same plan year, each employee, spouse and dependent covered under both plans is only counted once for purposes of the PCOR fee.

The IRS has created a helpful chart showing how the PCOR fee applies to common types of health plans.

Health Reimbursement Accounts (HRAs) - Nearly all HRAs are subject to the PCOR fee because they do not meet the conditions for exemption. An HRA will be exempt from the PCOR fee if it provides benefits only for dental or vision expenses, or it meets the following three conditions:

Health Flexible Spending Accounts (FSAs) - A health FSA is exempt from the PCOR fee if it satisfies an availability condition and a maximum benefit condition.

Additional special rules for HRAs and FSAs . Once an employer determines that its HRA or FSA is subject to the PCOR fee, the employer should consider the following special rules:

The IRS provides different rules for determining the average number of covered lives (i.e., employees, spouses and dependents) under insured plans versus self-insured plans. The same method must be used consistently for the duration of any policy or plan year. However, the insurer or sponsor is not required to use the same method from one year to the next.

A plan sponsor of a self-insured plan may use any of the following three

methods to determine the number of covered lives for a plan year:

1. Actual count method. Count the covered lives on each day of the plan year and divide by the number of days in the plan year.

Example: An employer has 900 covered lives on Jan. 1, 901 on Jan. 2, 890 on

Jan. 3, etc., and the sum of the lives covered under the plan on each day of

the plan year is 328,500. The average number of covered lives is 900 (328,500 ÷

365 days).

2. Snapshot method. Count the covered lives on a single day in each quarter (or more than one day) and divide the total by the number of dates on which a count was made. The date or dates must be consistent for each quarter. For example, if the last day of the first quarter is chosen, then the last day of the second, third and fourth quarters should be used as well.

Example: An employer has 900 covered lives on Jan. 15, 910 on April 15, 890 on

July 15, and 880 on Oct. 15. The average number of covered lives is 895 [(900 +

910+ 890+ 880) ÷ 4 days].

As an alternative to counting actual lives, an employer can count the number of

employees with self-only coverage on the designated dates, plus the number of

employees with other than self-only coverage multiplied by 2.35.

3. Form 5500 method. If a Form 5500 for a plan is filed before the due date of the Form 720 for that year, the plan sponsor can determine the number of covered lives based on the Form 5500. If the plan offers just self-only coverage, the plan sponsor adds the participant counts at the beginning and end of the year (lines 5 and 6d on Form 5500) and divides by 2. If the plan also offers family or dependent coverage, the plan sponsor adds the participant counts at the beginning and end of the year (lines 5 and 6d on Form 5500) without dividing by 2.

Example: An employer offers single and family coverage with a plan year ending

on Dec. 31. The 2013 Form 5500 is filed on June 5, 2014, and reports 132

participants on line 5 and 148 participants on line 6d. The number of covered

lives is 280 (132 + 148).

To evaluate liability for PCOR fees, plan sponsors should identify all of their plans that provide medical benefits and determine if each plan is insured or self-insured. If any plan is self-insured, the plan sponsor should take the following actions:

According to recent news reports, nearly half of the 17 Exchanges run by states and the District of Columbia under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) are struggling financially:

Many of the online exchanges are wrestling with surging costs, especially for balky technology and expensive customer call centers — and tepid enrollment numbers. To ease the fiscal distress, officials are considering raising fees on insurers, sharing costs with other states and pressing state lawmakers for cash infusions. Some are weighing turning over part or all of their troubled marketplaces to the federal exchange, HealthCare.gov, which now works smoothly.

Of course, many states can’t solve their financial troubles easily. As independent entities, their income depends on fees imposed on insurers, which is then often passed on to the consumer signing up for health care. However, those fees are entirely contingent on how many people enroll in that particular Exchange; low enrollment invariably means higher costs.

Low enrollment is where the trouble thickens. The recently completed open enrollment period only rose 12 percent to 2.8 million sign-ups for state Exchanges, according to The Washington Post. Comparatively, the federal Exchange saw an increase of 61 percent to 8.8 million people.

According to the Post, state Exchanges have operating budgets between “$28 million and $32 million”. Most of the money tends to go to call centers, “Enrollment can be a lengthy process — and in several states, contractors are paid by the minute. An even bigger cost involves IT work to correct defective software that might, for example, make mistakes in calculating subsidies.”

However, The Fiscal Times contends that, “Some states may be misusing Obamacare grants in order to keep their state insurance exchanges operating—potentially flouting a provision in the law requiring them to cover the costs of the exchanges themselves starting this year.”

In fact, the ACA provided about $4.8 billion in grants to help states build and promote their Exchanges. As the article explains, before this year, states could use the grant money on overhead costs. However, a new provision that went into effect in January 2015 says that states can’t use the grants on maintenance and staffing costs; grant money must be spent on design, development and implementation costs.

The Fiscal Times spotlights California as a prime example of why state Exchanges are in troubled waters:

One of the worst examples comes from California, where the state’s exchange has been touted the most successful in the country for enrolling thousands of people. Covered California has already used up about $1.1 billion in federal funding to get its exchange up and running and is now expected to run a nearly $80 million deficit by the end of the year, according to the Orange County Register. The state has already set aside about $200 million to cover that, but the long-term sustainability of the program is very much in question.

In addition, state Exchanges like Hawaii might have to switch to the federal Exchange, Healthcare.gov, because of on-going financial solvency issues. “This is a contingency that is being imposed on any state-based exchange that doesn’t have a funded sustainability plan in play,” said Jeff Kissel, CEO of the Hawaii Health Connector.

According to the Post, states with the lowest enrollment are facing the biggest financial problems:

Turning operations over to the federal Exchange seems to be a popular alternative, but it doesn’t come without a cost: $10 million per Exchange, to be exact.

Although there are many options for state Exchanges to consider, it is likely that they will hold off on any final decisions until after the Supreme Court decides King v. Burwell. In this case, the Chief Justices will make a ruling in June that could either send a lifeline to ACA or remove a fundamental pillar of the law by under-cutting its ability to extend health insurance coverage to millions of Americans through its subsidy program.

The appellants in the King v. Burwell case say that IRS rule conflicts with the statutory language set forth in the ACA, which limits subsidy payments to individuals or families that enroll in the state-based Exchanges only. If the Court relies on a literal interpretation of the ACA’s language, millions of Americans who live in more than half of the states where the federal Exchange operates will not receive subsidies, thus undoing a fundamental pillar of the law. (Read more about the court case here.)

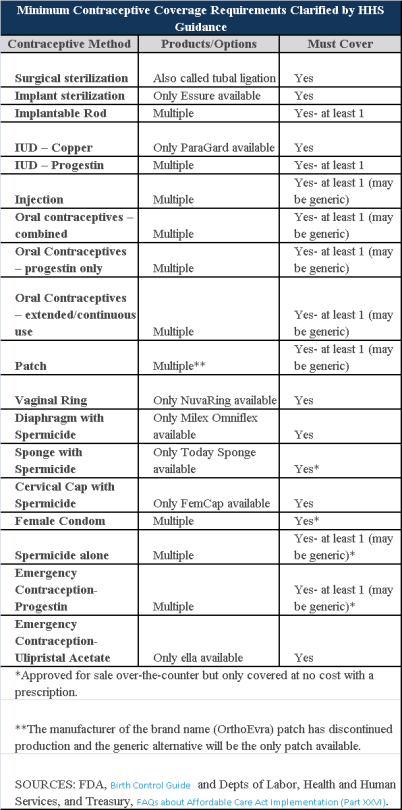

Plans and insurers must cover all 18 contraception methods approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, according to a new set of questions and answers on the Affordable Care Act’s preventive care coverage requirements.

“Reasonable medical management” still may be used to steer members to specific products within those methods of contraception. A plan or insurer may impose cost-sharing on non-preferred items within a given method, as long as at least one form of contraception in each method is covered without cost-sharing.

However, an individual’s physician must be allowed to override the plan’s drug management techniques if the physician finds it medically necessary to cover without cost-sharing an item that a given plan or insurer has classified as non-preferred, according to one of the frequently asked questions from the U.S. Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services and the Treasury.

The ACA mandated all plans and insurers to cover preventive care items, as defined by the Public Health Service Act, without cost-sharing. Eighteen forms of female contraception are included under the preventive care list. The individual FAQs on contraception clarified the following requirements.

The FAQ comes just weeks after reports and news coverage detailed health plan violations of the women coverage provisions of the ACA.

Testing and Dependent Care Answers

In questions separate from contraception, plans and insurers were told they must cover breast cancer susceptibility (BRCA-1 or BRCA-2) testing without cost-sharing. The test identifies whether the woman has genetic mutations that make her more susceptible to BRCA-related breast cancer.

Another question stated that if colonoscopies are performed as preventive screening without cost-sharing, then plans could not impose cost-sharing on the anesthesia component of that service.

The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) recently issued proposed new rules clarifying its stance on the interplay between the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and employer wellness programs. Officially called a “notice of proposed rulemaking” or NPRM, the new rules propose changes to the text of the EEOC’s ADA regulations and to the interpretive guidance explaining them.

If adopted, the NPRM will provide employers guidance on how they can use financial incentives or penalties to encourage employees to participate in wellness programs without violating the ADA, even if the programs include disability-related inquiries or medical examinations. This should be welcome news for employers, having spent nearly the past six years in limbo as a result of the EEOC’s virtual radio silence on this question.

A Brief History: How

Did We Get Here?

In 1990, the ADA was enacted to protect individuals with ADA-qualifying

disabilities from discrimination in the workplace. Under the ADA,

employers may conduct medical examinations and obtain medical histories as part

of their wellness programs so long as employee participation in them is

voluntary. The EEOC confirmed in 2000 that it considers a wellness

program voluntary, and therefore legal, where employees are neither required to

participate in it nor penalized for non-participation.

Then, in 2006, regulations were issued that exempted wellness programs from the nondiscrimination requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) so long as they met certain requirements. These regulations also authorized employers for the first time to offer financial incentives of up to 20% of the cost of coverage to employees to encourage them to participate in wellness programs.

But between 2006 and 2009 the EEOC waffled on the legality of these financial incentives, stating that “the HIPAA rule is appropriate because the ADA lacks specific standards on financial incentives” in one instance, and that the EEOC was “continuing to examine what level, if any, of financial inducement to participate in a wellness program would be permissible under the ADA” in another.

Shortly thereafter, the 2010 enactment of President Obama’s Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), which regulates corporate wellness programs, appeared to put this debate to rest. The ACA authorized employers to offer certain types of financial incentives to employees so long as the incentives did not exceed 30% of the cost of coverage to employees.

But in the years following the ACA’s enactment, the EEOC restated that it had not in fact taken any position on the legality of financial incentives. In the wake of this pronouncement, employers were left understandably confused and uncertain. To alleviate these sentiments, several federal agencies banded together and jointly issued regulations that authorized employers to reward employees for participating in wellness programs, including programs that involved medical examinations or questionnaires. These regulations also confirmed the previously set 30%–of-coverage ceiling and even provided for incentives of up to 50%of coverage for programs related to preventing or reducing the use of tobacco products.

After remaining silent about employer wellness programs for nearly five years, in August 2014, the EEOC awoke from its slumber and filed its very first lawsuit targeting wellness programs, EEOC v. Orion Energy Systems, alleging that they violate the ADA. In the following months, it filed similar suits against Flambeau, Inc., and Honeywell International, Inc. In EEOC v. Honeywell International, Inc., the EEOC took probably its most alarming position on the subject to date, asserting that a wellness program violates the ADA even if it fully complies with the ACA.

What’s In The NPRM?

According to EEOC Chair Jenny Yang, the purpose of the EEOC’s NPRM is to

reconcile HIPAA’s authorization of financial incentives to encourage

participation in wellness programs with the ADA’s requirement that medical

examinations and inquiries that are part of them be voluntary. To that

end, the NPRM explains:

Each of these parts of the NPRM is briefly discussed below.

What is an employee

wellness program?

In general, the term “wellness program” refers to a program or activity offered

by an employer to encourage its employees to improve their health and to reduce

overall health care costs. For instance, one program might encourage

employees to engage in healthier lifestyles, such as exercising daily, making

healthier diet choices, or quitting smoking. Another might obtain medical

information from them by asking them to complete health risk assessments or

undergo a screening for risk factors.

The NPRM defines wellness programs as programs that are reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease. To meet this standard, programs must have a reasonable chance of improving the health of, or preventing disease in, its participating employees. The programs also must not be overly burdensome, a pretext for violating anti-discrimination laws, or highly suspect in the method chosen to promote health or prevent disease.

How is voluntary

defined?

The NPRM contains several requirements that must be met in order for

participation in wellness programs to be voluntary. Specifically,

employers may not:

Additionally, for wellness programs that are part of a group health plan, employers must provide a notice to employees clearly explaining what medical information will be obtained, how it will be used, who will receive it, restrictions on its disclosure, and the protections in place to prevent its improper disclosure.

What incentives may

you offer?

The NPRM clarifies that the offer of limited incentives is permitted and will

not render wellness programs involuntary. Under the NPRM, the maximum

allowable incentive employers can offer employees for participation in a

wellness program or for achieving certain health results is 30% of the total

cost of coverage to employees who participate in it. The total cost of

coverage is the amount that the employer and the employee pay, not just the

employee’s share of the cost. The maximum allowable penalty employers may

impose on employees who do not participate in the wellness program is the

same.

What about

confidentiality?

The NPRM does not change any of the exceptions to the confidentiality

provisions in the EEOC’s existing ADA regulations. It does, however, add

a new subsection that explains that employers may only receive information

collected by wellness programs in aggregate form that does not disclose, and is

not likely to disclose, the identity of the employees participating in it,

except as may be necessary to administer the plan.

Additionally, for a wellness program that is part of a group health plan, the health information that identifies an individual is “protected health information” and therefore subject to HIPAA. HIPAA mandates that employers maintain certain safeguards to protect the privacy of such personal health information and limits the uses and disclosure of it.

Keep in mind that the NPRM revisions discussed above only clarify the EEOC’s stance regarding how employers can use financial incentives to encourage their employees to participate in employer wellness programs without violating the ADA. It does not relieve employers of their obligation to ensure that their wellness programs comply with other anti-discrimination laws as well.

Is This The Law?

The NPRM is just a notice that alerts the public that the EEOC intends to

revise its ADA regulations and interpretive guidance as they relate to employer

wellness programs. It is also an open invitation for comments regarding

the proposed revisions. Anyone who would like to comment on the NPRM must

do so by June 19, 2015. After that, the EEOC will evaluate all of the

comments that it receives and may make revisions to the NPRM in response to

them. The EEOC then votes on a final rule, and once it is approved, it

will be published in the Federal Register.

Since the NPRM is just a proposed rule, you do not have to comply with it just yet. But our advice is that you bring your wellness program into compliance with the NPRM for a few reasons. For one, it is very unlikely that the EEOC, or a court, would fault you for complying with the NPRM until the final rule is published. Additionally, many of the requirements that are set forth in the NPRM are already required under currently existing law. Thus, while waiting for the EEOC to issue its final rule, in the very least, you should make sure that you do not:

In addition you should provide reasonable accommodations to employees with disabilities to enable them to participate in wellness programs and obtain any incentives offered (e.g., if an employer has a deaf employee and attending a diet and exercise class is part of its wellness program, then the employer should provide a sign language interpreter to enable the deaf employee to participate in the class); and ensure that any medical information is maintained in a confidential manner.

During this year, businesses will be hearing a lot about the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA’s) information reporting requirements under Code Sections 6055 and 6056. Information gathering will be critical to successful reporting, and there is one aspect of that information gathering which employers might want to take action on sooner rather than later – collecting Social Security numbers (SSNs), particularly when required to do so from the spouses and dependents of their employees. There are, of course, ACA implications for not taking this step, as well as data privacy and security risks for employer and their vendors.

Under the ACA, providers of “minimum essential coverage” (MEC) must report certain information about that coverage to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), as well as to persons receiving that MEC. Employers that sponsor self-insured group health plans are providers of MEC for this purpose, and in the course of meeting the reporting requirements, must collect and report SSNs to the IRS. However, this reporting mandate requires those employers (or vendors acting on their behalf) to transmit to the IRS the SSNs of employee and their spouses and dependents covered under the plan, unless the employers either (i) exhaust reasonable collection efforts described below, (ii) or meet certain requirements for limited reporting overall.

Obviously, employers are familiar with collecting, using and disclosing employee SSNs for legitimate business and benefit plan purposes. Collecting SSNs from spouses and dependents will be an increased burden, creating more risk on employers given the increased amount of sensitive data they will be handling, and possibly from vendors working on their behalf. The reporting rules permit an employer to use a dependent’s date of birth, only if the employer was not able to obtain the SSN after “reasonable efforts.” For this purpose, reasonable efforts means the employer was not able to obtain the SSN after an initial attempt, and two subsequent attempts.

From an ACA standpoint, employers with self-insured plans that have not collected this information should be engaged in these efforts during the year (2015) to ensure they are ready either to report the SSNs, or the DOBs. At the same time, collecting more sensitive information about individuals raises data privacy and security risks for an organization regarding the likelihood and scope of a breach. Some of those risks, and steps employers could take to mitigate those risks, are described below.

Employers navigating through ACA compliance and reporting requirements have many issues to be considered. How personal information or protected health information is safeguarded in the course of those efforts is one more important consideration.

The IRS and the Treasury Department issued a notice on the so-called “Cadillac Tax”—a 40 percent excise tax to be imposed on high-cost employer-sponsored health plans beginning in 2018 under the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

Notice 2015-16, released on Feb. 23, 2015, discusses a number of issues concerning the tax and requests comments on the possible approaches that ultimately could be incorporated in proposed regulations. Specifically, the guidance states that the agencies anticipate that pretax salary reduction contributions made by employees to health savings accounts (HSAs) will be subject to the Cadillac tax.

Background

In 2018, the ACA provides that a nondeductible 40 percent excise tax be imposed on “applicable employer-sponsored coverage” in excess of statutory thresholds (in 2018, $10,200 for self-only, $27,500 for family). As 2018 approaches, the benefit community has long awaited guidance on this tax. While many employers have actively managed their plan offerings and costs in anticipation of the impact of the tax, those efforts have been hampered by the lack of guidance. Among other things, employers are uncertain what health coverage is subject to the tax and how the tax is calculated.

Particularly, Notice 2015-16 addresses:

The agencies are requesting comments on issues

discussed in this notice by May 15, 2015. They intend to issue another notice

that will address other areas of the excise tax and anticipates issuing

proposed regulations after considering public comments on both notices.

Applicable Coverage

Of most immediate interest to plan sponsors is the specific type of coverage (i.e., “applicable coverage”) that will be subject to the excise tax, particularly where the statute is unclear.

Employee Pretax HSA

Contributions

The ACA statute provides that employer contributions to an HSA are subject to

the excise tax, but did not specifically address the treatment of employee

pretax HSA contributions. The notice says that the agencies “anticipate that

future proposed regulations will provide that (1) employer contributions to

HSAs, including salary reduction contributions to HSAs, are included in

applicable coverage, and (2) employee after-tax contributions to HSAs are

excluded from applicable coverage.”

Note: This anticipated treatment of employee pretax contributions to HSAs will have a significant impact on HSA programs. If implemented as the agencies anticipate, it could mean many employer plans that provide for HSA contributions will be subject to the excise tax as early as 2018, unless the employer limits the amount an employee can contribute on a pretax basis.

Self-Insured Dental

and Vision Plans

The ACA statutory language specifically excludes fully insured dental and

vision plans from the excise tax. The treatment of self-insured dental and

vision plans was not clear. The notice states that the agencies will consider

exercising their “regulatory authority” to exclude self-insured plans that

qualify as excepted benefits from the excise tax.

Employee Assistance

Programs

The agencies are also considering whether to exclude excepted-benefit employee

assistance programs (EAPs) from the excise tax.

Onsite Medical Clinics

The notice discusses the exclusion of certain onsite medical clinics that offer

only de

minimis care to employees,

citing a provision in the COBRA regulations, and anticipates excluding such

clinics from applicable coverage. Under the COBRA regulations an onsite clinic

is not considered a group health plan if:

The agencies are also asking for comment on

the treatment of clinics that provide certain services in addition to first

aid:

In Closing

With the release of this initial guidance, plan sponsors can gain some insight into the direction the government is likely to take in proposed regulations and can better address potential plan design strategie

Even small employers notsubject to the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) coverage mandate can’t reimburse employees for nongroup health insurance coverage purchased on a public exchange, the Internal Revenue Service confirmed. But small employers providing premium reimbursement in 2014 are being offered transition relief through mid-2015.

IRS Notice 2015-17, issued on Feb. 18, 2015, is another in a series of guidance from the IRS reminding employers that they will run afoul of the ACA if they use health reimbursement arrangements (HRAs) or other employer payment plans—whether with pretax or post-tax dollars—to reimburse employees for individual policy premiums, including policies available on ACA federal or state public exchanges.

This time the warning is aimed at small employers—those with fewer than 50 full-time employees or equivalent workers. While small organizations are not subject to the ACA’s “shared responsibility” employer mandate to provide coverage or pay a penalty (aka Pay or Play), if they do provide health coverage it must meet a range of ACA coverage requirements.

“The agencies have taken the position that employer payment plans are group health plans, and thus must comply with the ACA’s market reforms,” noted Timothy Jost, J.D., a professor at the Washington and Lee University School of Law, in a Feb. 19 post on the Health Affairs Blog. “A group health plan must under these reforms cover at least preventive care and may not have annual dollar limits. A premium payment-only HRA or other payment arrangement that simply pays employee premiums does not comply with these requirements. An employer that offers such an arrangement, therefore, is subject to a fine of $100 per employee per day. (An HRA integrated into a group health plan that, for example, helps with covering cost-sharing is not a problem).”

Transition Relief

The notice provides transition relief for small employers that used premium payment arrangements for 2014. Small employers also will not be subject to penalties for providing payment arrangements for Jan. 1 through June 30, 2015. These employers must end their premium reimbursement plans by that time. This relief does not extend to stand-alone HRAs or other arrangements used to reimburse employees for medical expenses other than insurance premiums.

No similar relief was given for large employers (those with 50 or more full-time employees or equivalents) for the $100 per day per employee penalties. Large employers are required to self-report their violation on the IRS’s excise tax form 8928 with their quarterly filings.

“Notice 2015-17 recognizes that impermissible premium-reimbursement arrangements have been relatively common, particularly in the small-employer market,” states a benefits brief from law firm Spencer Fane. “And although the ACA created “SHOP Marketplaces” as a place for small employers to purchase affordable [group] health insurance, the notice concedes that the SHOPs have been slow to get off the ground. Hence, this transition relief.”

Subchapter S Corps.

The notice states that Subchapter S closely held corporations may pay for or reimburse individual plan premiums for employee-shareholders who own at least 2 percent of the corporation. “In this situation, the payment is included in income, but the 2-percent shareholder can deduct the premiums for tax purposes,” Jost explained. The 2-percent shareholder may also be eligible for premium tax credits through the marketplace SHOP Marketplace if he or she meets other eligibility requirements.

Tricare

Employers can pay for some or all of the expenses of employees covered by Tricare—a Department of Defense program that provides civilian health benefits for military personnel (including some members of the reserves), military retirees and their dependents—if the payment plan is integrated with a group health plan that meets ACA coverage requirements.

Higher Pay Is Still OK

One option that the IRS will allow employers is to simply increase an employee’s taxable wages in lieu of offering health insurance. “As long as the money is not specifically designated for premiums, this would not be a premium payment plan,” said Jost. “The employer could even give the employee general information about the marketplace and the availability of premium tax credits as long as it does not direct the employee to a specific plan.”

But if the employer pays or reimburses premiums specifically, “even if the payments are made on an after-tax basis, the arrangement is a noncompliant group health plan and the employer that offers it is subject to the $100 per day per employee penalty,” Jost warned.

“Small employers now have just over four months in which to wind down any impermissible premium-reimbursement arrangement,” the Spencer Fane brief notes. “In its place, they may wish to adopt a plan through a SHOP Marketplace. Although individuals may enroll through a Marketplace during only annual or special enrollment periods, there is no such limitation on an employer’s ability to adopt a plan through a SHOP.”

Form 1095-A is a tax form that will be sent to consumers who have been enrolled in health insurance through the Marketplace in the past year. Just like employees receive a W-2 from their employer, consumer who had a plans on the Marketplace will also receive form 1095-A from the Marketplace, which they will need for taxes. Similar to how households receive multiple W-2s if individuals have multiple jobs, some households will get multiple Form 1095-As if they were covered under different plans or changed plans during the year. The 1095-A forms will be mailed direct to consumer’s last known home address provided to the Marketplace and will be postmarked by February 2, 2015.

Form 1095-A provides information to consumers that is needed to complete Form 8962, Premium Tax Credit (PTC). The Marketplace has also reporting this information to the IRS. Consumers will file Form 8962 with their tax returns if they want to claim the premium tax credit or if they received premium assistance through advance credit payments made to their insurance provider.