On July 22, 2019, the IRS announced that the ACA affordability percentage for the 2020 calendar year will decrease to 9.78%. The current rate for the 2019 calendar year is 9.86%.

As a reminder, under the Affordable Care Act’s employer mandate, an applicable large employer is generally required to offer at least one health plan that provides affordable, minimum value coverage to its full-time employees (and minimum essential coverage to their dependents) or pay a penalty. For this purpose, “affordable” means the premium for self-only coverage cannot be greater than a specified percentage of the employee’s household income. Based on this recent guidance, that percentage will be 9.78% for the 2020 calendar year.

Employers now have the tools to evaluate the affordability of their plans for 2020. Unfortunately, for some employers, a reduction in the affordability percentage will mean that they will have to reduce what employees pay for employee only coverage, if they want their plans to be affordable in 2020.

For example, in 2019 an employer using the hourly rate of pay safe harbor to determine affordability can charge an employee earning $12 per hour up to $153.81 ($12 X 130= 1560 X 9.86%) per month for employee-only coverage. However in 2020, that same employer can only charge an employee earning $12 per hour $152.56 ($12 X 130= 1560 X 9.78%) per month for employee-only coverage, and still use that safe harbor. A reduction in the affordability percentage presents challenges especially for plans with non-calendar year renewals, as those employers that are subject to the ACA employer mandate may need to change their contribution percentage in the middle of their benefit plan year to meet the new affordability percentage. For this reason, we recommend that employers re-evaluate what changes, if any, they should make to their employee contributions to ensure their plans remain affordable under the ACA.

As we have written about previously, employers will sometimes use the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) safe harbor to determine affordability. While we won’t know the 2020 FPL until sometime in early 2020, employers are allowed to use the FPL in effect at least six months before the beginning of their plan year. This means employers can use the 2019 FPL number as a benchmark for determining affordability for 2020 now that they know what the affordability percentage is for 2020.

The IRS has recently issued Notice 2019-45, which increases the scope of preventive care that can be covered by a high deductible health plan (“HDHP”) without eliminating the covered person’s ability to maintain a health savings account (“HSA”).

Since 2003, eligible individuals whose sole health coverage is a HDHP have been able to contribute to HSAs. The contribution to the HSA is not taxed when it goes into the HSA or when it is used to pay health benefits. It can for example be used to pay deductibles or copays under the HDHP. But it can also be used as a kind of supplemental retirement plan to pay Medicare premiums or other health expenses in retirement, in which case it is more tax-favored than even a regular retirement plan.

As the name suggests, a HDHP must have a deductible that exceeds certain minimums ($1,350 for self-only HDHP coverage and $2,700 for family HDHP coverage for 2019, subject to cost of living changes in future years). However, certain preventive care (for example, annual physicals and many vaccinations) is covered without having to meet the deductible. In general, “preventive care” has been defined as care designed to identify or prevent illness, injury, or a medical condition, as opposed to care designed to treat an existing illness, injury, or condition.

Notice 2019-45 expands the existing definition of preventive care to cover medical expenses which, although they may treat a particular existing chronic condition, will prevent a future secondary condition. For example, untreated diabetes can cause heart disease, blindness, or a need for amputation, among other complications. Under the new guidance, a HDHP will cover insulin, treating it as a preventative for those other conditions as opposed to a treatment for diabetes.

The Notices states that in general, the intent was to permit the coverage of preventive services if:

The Notice is in general good news for those covered by HDHPs. However, it has two major limitations:

Given the expansion of the types of preventive coverage that a HDHP can cover, and the tax advantages of an HSA to employees, employers who have not previously implemented a HDHP or HSA may want to consider doing so now. However, as with any employee benefit, it is important to consider both the potential demand for the benefit and the administrative cost.

To help protect people from identity theft, the Internal Revenue Service has issued a final rule that will allow employers to shorten Social Security numbers (SSNs) or alternative taxpayer identification numbers (TINs) on Form W-2 wage and tax statements that are distributed to employees, beginning in 2021.

The IRS published the new rule in the Federal Register on July 3. It finalizes a proposed rule issued in September 2017 with no substantive changes.

Under the regulation, SSNs or other TINs can be masked with the first five digits of the nine-digit number replaced with asterisks or XXXs in the following formats:

To ensure that accurate wage information is reported to the IRS and the Social Security Administration (SSA), the rule does not permit truncated TINs on W-2 forms sent to those agencies. The IRS said that instructions to W-2 forms will be updated to reflect these regulations and explained that masking the numbers on employees’ forms is not mandatory.

The IRS already allows employers to use truncated TINs on employees’ Form 1095-C for Affordable Care Act reporting and on certain other tax-related statements distributed to employees.

The IRS delayed the applicability date of the final rule to apply to W-2 forms that are required to be furnished to employees after Dec. 31, 2020, “so employers still have time to decide whether to implement the change,” according to attorneys at Washington, D.C., law firm Covington & Burling. “The delayed effective date is intended to allow states and local governments time to update their rules to permit the use of truncated TINs, if they do not already do so,” the attorneys wrote.

Permitting employers to truncate Social Security numbers on Forms W-2 provided to employees will better protect individuals’ sensitive personal information.

But some fear that the change could hamper accurate reporting to government agencies. Concerns have been raised that employees who already receive masked pay statements will have no means of ensuring that their SSN is entered (and subsequently reported to the SSA and IRS) correctly. According to the SSA website, a SSN correction is a common error and even if an SSN is ‘verified,’ it could still be entered into payroll software incorrectly. The W2 provides a means for the employee to catch that mistake.

The IRS responded that the benefits of allowing employers to protect their employees from identity theft by truncating employees’ SSNs outweighed the risks of unintended consequences, and that many of the potential consequences noted by the commenters could be mitigated by using other methods to verify a taxpayer’s identity and the accuracy of the taxpayers’ information.

Some believe the new rule does not go far enough by making truncated Social Security numbers or other TINs an option rather than a requirement. W-2 forms have been the target of several high-profile breaches, and therefore the IRS should only permit truncated SSNs to protect employees from future breaches according to the Electronic Privacy Information Center in Washington, D.C.

Advocates claim a newly issued regulation could transform how employers pay for employee health care coverage.

On June 13, the U.S. Departments of Health and Human Services, Labor and the Treasury issued a final rule allowing employers of all sizes that do not offer a group coverage plan to fund a new kind of health reimbursement arrangement (HRA), known as an individual coverage HRA (ICHRA). The departments also posted FAQs on the new rule.

Starting Jan. 1, 2020, employees will be able to use employer-funded ICHRAs to buy individual-market insurance, including insurance purchased on the public exchanges formed under the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

Under IRS guidance from the Obama administration (IRS Notice 2013-54), employers were effectively prevented from offering stand-alone HRAs that allow employees to purchase coverage on the individual market.

“Using an individual coverage HRA, employers will be able to provide their workers and their workers’ families with tax-preferred funds to pay all or a portion of the cost of coverage that workers purchase in the individual market,” said Joe Grogan, director of the White House Domestic Policy Council. “The departments estimate that once employers fully adjust to the new rules, roughly 800,000 employers will offer individual coverage HRAs to pay for insurance for more than 11 million employees and their family members, providing them with more options for selecting health insurance coverage that better meets their needs.”

The new rule “is primarily about increasing employer flexibility and worker choice of coverage,” said Brian Blase, special assistant to the president for health care policy. “We expect this rule to particularly benefit small employers and make it easier for them to compete with larger businesses by creating another option for financing worker health insurance coverage.”

The final rule is in response to the Trump administration’s October 2017 executive order on health care choice and competition, which resulted in an earlier final rule on association health plans that is now being challenged in the courts, and a final rule allowing low-cost short-term insurance that provides less coverage than a standard ACA plan.

New Types of HRAs

Existing HRAs are employer-funded accounts that employees can use to pay out-of-pocket health care expenses but may not use to pay insurance premiums. Unlike health savings accounts (HSAs), all HRAs, including the new ICHRA, are exclusively employer-funded, and, when employees leave the organization, their HRA funds go back to the employer. This differs from HSAs, which are employee-owned and portable when employees leave.

The proposed regulations keep the kinds of HRAs currently permitted (such as HRAs integrated with group health plans and retiree-only HRAs) and would recognize two new types of HRAs:

What ICHRAs Can Do

Under the new HRA rule:

The rule also includes a disclosure provision to help ensure that employees understand the type of HRA being offered by their employer and how the ICHRA offer may make them ineligible for a premium tax credit or subsidy when buying an ACA exchange-based plan. To help satisfy the notice requirements, the IRS issued an Individual Coverage HRA Model Notice.

QSEHRAs and ICHRAs

Currently, qualified small-employer HRAs (QSEHRAs), created by Congress in December 2016, allow small businesses with fewer than 50 full-time employees to use pretax dollars to reimburse employees who buy nongroup health coverage. The new rule goes farther and:

The legislation creating QSEHRAs set a maximum annual contribution limit with inflation-based adjustments. In 2019, annual employer contributions to QSEHRAs are capped at $5,150 for a single employee and $10,450 for an employee with a family.

The new rule, however, doesn’t cap contributions for ICHRAs.

As a result, employers with fewer than 50 full-time employees will have two choices—QSEHRAs or ICHRAs—with some regulatory differences between the two. For example:

“QSEHRAs have a special rule that allows employees to qualify for both their employer’s subsidy and the difference between that amount and any premium tax credit for which they’re eligible,” said John Barkett, director of policy affairs at consultancy Willis Towers Watson.

While the ability of employees to couple QSEHRAs with a premium tax credit is appealing, the downside is QSEHRA’s annual contribution limits, Barkett said. “QSEHRA’s are limited in their ability to fully subsidize coverage for older employees and employees with families, because employers could run through those caps fairly quickly,” he noted.

For older employees, the least expensive plan available on the individual market could easily cost $700 a month or $8,400 a year, Barkett pointed out, and “with a QSEHRA, an employer could only put in around $429 per month to stay under the $5,150 annual limit for self-only coverage.”

Similarly, for employees with many dependents, premiums could easily exceed the QSEHRA’s family coverage maximum of $10,450, whereas “all those dollars could be contributed pretax through an ICHRA,” Barkett said.

An Excepted-Benefit HRA

In addition to allowing ICHRAs, the final rule creates a new excepted-benefit HRA that lets employers that offer traditional group health plans provide an additional pretax $1,800 per year (indexed to inflation after 2020) to reimburse employees for certain qualified medical expenses, including premiums for vision, dental, and short-term, limited-duration insurance.

The new excepted-benefit HRAs can be used by employees whether or not they enroll in a traditional group health plan, and can be used to reimburse employees’ COBRA continuation coverage premiums and short-term insurance coverage plan premiums.

Safe Harbor Coming

With ICHRAs, employers still must satisfy the ACA’s affordability and minimum value requirements, just as they must do when offering a group health plan. However, “the IRS has signaled it will come out with a safe harbor that should make it straightforward for employers to determine whether their ICHRA offering would comply with ACA coverage requirements,” Barkett said.

Last year, the IRS issued Notice 2018-88, which outlined proposed safe harbor methods for determining whether individual coverage HRAs meet the ACA’s affordability threshold for employees, and which stated that ICHRAs that meet the affordability standard will be deemed to offer at least minimum value.

The IRS indicated that further rulemaking on these safe harbor methods is on its agenda for later this year.

The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) fee for 2018 is due by July 31, 2019. For groups whose plan year ended December 31, 2018 this will be the final PCORI payment they will have to make. Health plans whose plan year ended after December 31, 2018, but before October 1, 2019, will still have one final PCORI payment that will be due by July 31, 2020.

The PCORI fee is imposed under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) on issuers of certain health insurance policies and self-insured health plan sponsors to help fund the research institute. The fee amount is based on the average number of covered lives under the policy or plan, and the total (along with the fee) must be reported annually on the second quarter IRS Form 720 (Quarterly Federal Excise Tax Return) and paid by July 31. The fee due July 31, 2019 is calculated as $2.45 per covered life. Plan sponsors must pay the PCORI fee by July 31 of the calendar year immediately following the calendar year in which the plan year ends.

For fully insured health plans, the insurance carrier files Form 720 and pays the PCORI fee. So, employers with fully insured health plans have no filing requirement (but will be charged by the carrier for the fee). Employers that sponsor self-insured health plans are responsible for filing Form 720 and paying their due PCORI fee. For self-insured plans with multiple employers, the named plan sponsor is generally required to file Form 720.

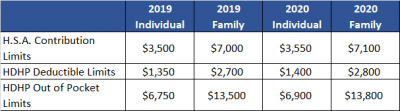

The fee may not be paid from plan assets, so it must be paid out of the sponsor’s general assets. According to the IRS, however, the fee is a tax-deductible business expense for employers with self-insured plans.Late May 2019, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) announced the 2020 limits for contributions to Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) and limits for High Deductible Health Plans (HDHPs). These inflation adjustments are provided for under Internal Revenue Code Section 223.

For the 2020 calendar year, an HDHP is a health plan with an annual deductible that is not less than $1,400 for self-only coverage and $2,800 for family coverage. 2020 annual out-of-pocket expenses (deductibles, copayments and other amounts, excluding premiums) cannot exceed $6,900 for self-only coverage and $13,800 for family coverage.

For individuals with self-only coverage under an HDHP, the 2020 annual contribution limit to an HSA is $3,550 and for an individual with family coverage, the HSA contribution limit is $7,100.

No change was announced to the HSA catch-up contribution limit. If an individual is age 55 or older by the end of the calendar year, he or she can contribute an additional $1,000 to his or her HSA. If married and both spouses are age 55, each individual can contribute an additional $1,000 into his or her individual account.

For married couples that have family coverage where both spouses are over age 55, each spouse can take advantage of the $1,000 catch-up, but in order to get the full $9,100 contribution, they will need to use two accounts. The contribution cannot be maximized with only one account. One individual would contribute the family coverage maximum plus his or her individual catch-up, and the other would contribute the catch-up maximum to his or her individual account.

The Social Security Administration (SSA) recently resurrected its practice of issuing Employer Correction Request notices – also known as “no-match letters” – when it receives employee information from an employer that does not match its records. If you find yourself in receipt of such a letter, it is recommended that you take the following seven steps as well as considering consulting your legal counsel.

Step 1: Understand The Letter

The first and perhaps most obvious step is to read the letter carefully and understand what it says. Too often employers rush into action before taking the time to read and understand the no-match letter.

(more…)