Page 1 of 2

Both the IRS and the three agencies tasked with issuing rules under the Affordable Care Act (“ACA”) have released guidance on new items considered preventive and medical care, as well as some further requirements around existing items plans are required to cover. Some of the guidance related to high deductible health plans (“HDHPs”) is effective retroactively presumably because some HDHPs may have already covered those items believing them to be preventive care.

Additional Medical and Preventive Care

In IRS Notice 2024-71, the IRS created a safe harbor stating that male condoms will be considered medical care for tax purposes. Among other results, this means that health plans, health flexible spending arrangements (“Health FSAs”), health reimbursement arrangements (“HRAs”), and health savings accounts (“HSAs”) can pay for or reimburse the cost of male condoms on a tax-free basis. The notice doesn’t specify an effective date, but presumably it is effective immediately.

However, for them to be preventive care for purposes of high deductible health plans and HSA purposes, separate guidance is required. As a reminder, for an individual to contribute to an HSA, they must be covered by a HDHP and not be covered by other non-permitted health insurance. Therefore, even though the IRS has now said that male condoms are medical care, they cannot be covered before the deductible under an HDHP without additional guidance.

Fortunately, the IRS also issued Notice 2024-75. It includes that needed guidance and some other items as well. Specifically, HDHPs can now cover the following items as preventive care before the individual satisfies the deductible:

The retroactive dates were presumably intended to address concerns that plans had already covered some of these items. However, to be clear, HDHPs are not required to cover these items pre-deductible, but this guidance allows them to do so without affecting a participant’s ability to contribute to an HSA.

FAQs part 68

In addition, the Departments of Health and Human Services, Labor, and Treasury issued guidance on some existing items plans are required to cover in their sixty-eighth edition of ACA FAQs.

For plans subject to the Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act (“WHCRA”), the FAQs clarify that plans are required to cover chest wall reconstruction with an aesthetic flat closure, if elected by the patient in consultation with the attending physician. Under WHCRA, plans are generally required to cover reconstruction of the breast on which a mastectomy was performed, and surgery and reconstruction of the other breast to produce a symmetrical appearance. The guidance now confirms that this requirement includes providing an aesthetic flat closure, where extra tissues in the breast area are removed, and the remaining tissue is tightened and smoothed out to create a flat chest wall. Most plans are subject to WHCRA, including governmental plans, unless they are self-funded and have opted out. Church plans that have elected not to be subject to ERISA are not subject to WHCRA.

The FAQs address some common coding practices for items that are deemed to be medical care. The specifics and nuances of this guidance are more relevant to carriers or third party administrators (“TPAs”). However, in general, if an item is coded as preventive, it should be treated as such unless there’s additional information in the claim that would lead the plan or carrier to believe it should not be treated as preventive. If an item or service is not covered as preventive when it should be, participants and beneficiaries have the right to appeal under the relevant plan claims procedures.

Takeaways

Employers should work with their insurance carriers and TPAs to determine whether and how they plan to cover the additional permitted items for health FSAs, HRAs, and HDHPs. They should also address the coverage of the additional mandatory items from the FAQ guidance. Changes to plan documents, summary plan descriptions, or other communications may be required.

Transparency in Coverage mandates and COVID-19 considerations continue to dominate the discussion in the employee benefits compliance space this summer, but an “old faithful” reporting requirement looms soon: the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) filing and fee. The Affordable Care Act imposes this annual per-enrollee fee on insurers and sponsors of self-funded medical plans to fund research into the comparative effectiveness of various medical treatment options.

The typical due date for the PCORI fee is July 31, but because that date falls on a Sunday in 2022, the effective due date is pushed to the next business day, which is Aug. 1.

The filing and payment due by Aug. 1, 2022, is required for policy and plan years that ended during the 2021 calendar year. For plan years that ended Jan. 1, 2021 – Sept. 30, 2021, the fee is $2.66 per covered life. For plan years that ended Oct. 1, 2021 – Dec. 31, 2021 (including calendar year plans that ended Dec. 31, 2021), the fee is calculated at $2.79 per covered life.

Insurers report on and pay the fee for fully insured group medical plans. For self-funded plans, the employer or plan sponsor submits the fee and accompanying paperwork to the IRS. Third-party reporting and payment of the fee (for example, by the self-insured plan sponsor’s third-party claim payor) is not permitted.

An employer that sponsors a self-insured health reimbursement arrangement (HRA) along with a fully insured medical plan must pay PCORI fees based on the number of employees (dependents are not included in this count) participating in the HRA, while the insurer pays the PCORI fee on the individuals (including dependents) covered under the insured plan. Where an employer maintains an HRA along with a self-funded medical plan and both have the same plan year, the employer pays a single PCORI fee based on the number of covered lives in the self-funded medical plan and the HRA is disregarded.

The IRS collects the fee from the insurer or, in the case of self-funded plans, the plan sponsor in the same way many other excise taxes are collected. Although the PCORI fee is paid annually, it is reported (and paid) with the Form 720 filing for the second calendar quarter (the quarter ending June 30). Again, the filing and payment is typically due by July 31 of the year following the last day of the plan year to which the payment relates, but this year the due date pushes to Aug. 1.

IRS regulations provide three options for determining the average number of covered lives: actual count, snapshot and Form 5500 method.

Actual count: The average daily number of covered lives during the plan year. The plan sponsor takes the sum of covered lives on each day of the plan year and divides the number by the days in the plan year.

Snapshot: The sum of the number of covered lives on a single day (or multiple days, at the plan sponsor’s election) within each quarter of the plan year, divided by the number of snapshot days for the year. Here, the sponsor may calculate the actual number of covered lives, or it may take the sum of (i) individuals with self-only coverage, and (ii) the number of enrollees with coverage other than self-only (employee-plus one, employee-plus family, etc.), and multiply by 2.35. Further, final rules allow the dates used in the second, third and fourth calendar quarters to fall within three days of the date used for the first quarter (in order to account for weekends and holidays). The 30th and 31st days of the month are both treated as the last day of the month when determining the corresponding snapshot day in a month that has fewer than 31 days.

Form 5500: If the plan offers family coverage, the sponsor simply reports and pays the fee on the sum of the participants as of the first and last days of the year (recall that dependents are not reflected in the participant count on the Form 5500). There is no averaging. In short, the sponsor is multiplying its participant count by two, to roughly account for covered dependents.

The U.S. Department of Labor says the PCORI fee cannot be paid from ERISA plan assets, except in the case of union-affiliated multiemployer plans. In other words, the PCORI fee must be paid by the plan sponsor; it cannot be paid in whole or part by participant contributions or from a trust holding ERISA plan assets. The PCORI expense should not be included in the plan’s cost when computing the plan’s COBRA premium. The IRS has indicated the fee is, however, a tax-deductible business expense for sponsors of self-funded plans.

Although the DOL’s position relates to ERISA plans, please note the PCORI fee applies to non-ERISA plans as well and to plans to which the ACA’s market reform rules don’t apply, like retiree-only plans.

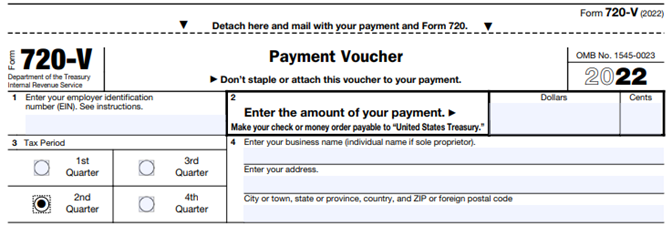

The filing and remittance process to the IRS is straightforward and unchanged from last year. On Page 2 of Form 720, under Part II, the employer designates the average number of covered lives under its “applicable self-insured plan.” As described above, the number of covered lives is multiplied by the applicable per-covered-life rate (depending on when in 2021 the plan year ended) to determine the total fee owed to the IRS.

The Payment Voucher (720-V) should indicate the tax period for the fee is “2nd Quarter.”

Failure to properly designate “2nd Quarter” on the voucher will result in the IRS’ software generating a tardy filing notice, with all the incumbent aggravation on the employer to correct the matter with IRS.

An employer that overlooks reporting and payment of the PCORI fee by its due date should immediately, upon realizing the oversight, file Form 720 and pay the fee (or file a corrected Form 720 to report and pay the fee, if the employer timely filed the form for other reasons but neglected to report and pay the PCORI fee). Remember to use the Form 720 for the appropriate tax year to ensure that the appropriate fee per covered life is noted.

The IRS might levy interest and penalties for a late filing and payment, but it has the authority to waive penalties for good cause. The IRS’s penalties for failure to file or pay are described here.

The IRS has specifically audited employers for PCORI fee payment and filing obligations. Be sure, if you are filing with respect to a self-funded program, to retain documentation establishing how you determined the amount payable and how you calculated the participant count for the applicable plan year.

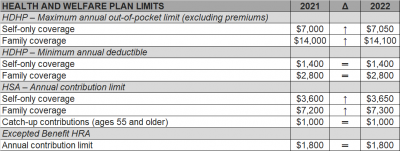

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) recently announced (See Revenue Procedure 2021-25) cost-of-living adjustments to the applicable dollar limits for health savings accounts (HSAs), high-deductible health plans (HDHPs) and excepted benefit health reimbursement arrangements (HRAs) for 2022. Many of the dollar limits currently in effect for 2021 will change for 2022. The HSA catch-up contribution for individuals ages 55 and older will not change as it is not subject to cost-of-living adjustments.

The table below compares the applicable dollar limits for HSAs, HDHPs and excepted benefit HRAs for 2021 and 2022.

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES ACT) was signed into law by the President on Friday.

There are three direct inclusions that immediately expand the usage of health savings accounts (HSA), flexible spending accounts (FSA), and health reimbursement arrangements (HRA) for employees.

1. Telehealth services can now be covered pre-deductible under a High Deductible Health Plan. The end date of this provision is Dec 21, 2021.

2. Over the counter (OTC) drugs and medicines are now eligible for reimbursement from an HSA, FSA or HRA. This is a permanent change.

3. Menstrual products are now eligible for reimbursement from an HSA, FSA or HRA. This is a permanent change.

Health Reimbursement Arrangements (HRAs) are account-based health plans funded with employer contributions to reimburse eligible participants and dependents for medical expenses. Prior to the Affordable Care Act, HRAs were not uncommon.

After the ACA, however, HRAs – which were classified as group health plans (GHPs) – had to satisfy the ACA’s market reform requirements, such as the prohibition against annual limits. Thus, unless an HRA was integrated with a GHP, HRAs usually could not satisfy these requirements alone.

On June 13, the Departments of Treasury, Labor, and Health and Human Services issued final regulations regarding HRAs, which will be effective on January 1, 2020. The regulations discuss two types of HRAs: (1) the individual coverage HRA (ICHRA); and (2) the expected benefit HRA.

An ICHRA can satisfy GHP requirements by integrating the HRA with individual market coverage or Medicare. The expected benefit HRA permits an employee to obtain excepted benefits like dental, vision, or short-term limited-duration insurance with an HRA. This article will focus on ICHRAs.

In order to offer an ICHRA, employers must ensure that a number of requirements are satisfied. For example, all individuals covered by the HRA need to be enrolled in individual health insurance or Medicare. Additionally, before any reimbursements are made, the employer must substantiate such enrollment with documentation from a third party or the participant’s attestation. An attestation, however, must be disregarded, if the employer has actual knowledge that the individual is not enrolled in eligible coverage.

Additionally, HRA coverage must be offered uniformly on the same terms and conditions to all employees in the class. Classes will be discussed in more detail below, but the regulations permit an employer to increase the maximum benefit for (1) older participants if that increase applies to all similarly aged participants in that class, and (2) participants with more dependents.

Further, being covered by an ICHRA will make an individual ineligible for a Premium Tax Credit (PTC). For this reason, the regulations have numerous notice requirements. First, employers must provide notice to eligible ICHRA employees 90 days before the beginning of a plan year that their participation in the ICHRA will make them ineligible for a PTC. For newly eligible employees, the notice must be provided no later than the date they are first eligible to participate. Moreover, there must be an opt-out provision at least annually and upon termination.

The ICHRA regulations make it possible for employers to offer an HRA to a certain class of employees and a traditional GHP to another class. It is important to note that an employer may not offer the same class of employees the option of an ICHRA or a traditional GHP.

The regulations also provide strict rules regarding how to define classes. The classes must be of a minimum size based on the number of employees the employer has:

Additionally, the classes must be based on named classes in the regulations which are based on objective criteria:

The regulations also clarify that employers may still offer retiree-only HRAs and they will not be subject to the ICHRA rules.

Given that there is a notice requirement and that open enrollment for plans that begin January 1, 2020 will generally begin in the fall, employers that would like to implement an ICHRA would likely have to start making plan design decisions soon. Even though the concept of an HRA may be familiar to many employers, these new regulations are nuanced, and employers will likely need assistance to navigate them.

Advocates claim a newly issued regulation could transform how employers pay for employee health care coverage.

On June 13, the U.S. Departments of Health and Human Services, Labor and the Treasury issued a final rule allowing employers of all sizes that do not offer a group coverage plan to fund a new kind of health reimbursement arrangement (HRA), known as an individual coverage HRA (ICHRA). The departments also posted FAQs on the new rule.

Starting Jan. 1, 2020, employees will be able to use employer-funded ICHRAs to buy individual-market insurance, including insurance purchased on the public exchanges formed under the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

Under IRS guidance from the Obama administration (IRS Notice 2013-54), employers were effectively prevented from offering stand-alone HRAs that allow employees to purchase coverage on the individual market.

“Using an individual coverage HRA, employers will be able to provide their workers and their workers’ families with tax-preferred funds to pay all or a portion of the cost of coverage that workers purchase in the individual market,” said Joe Grogan, director of the White House Domestic Policy Council. “The departments estimate that once employers fully adjust to the new rules, roughly 800,000 employers will offer individual coverage HRAs to pay for insurance for more than 11 million employees and their family members, providing them with more options for selecting health insurance coverage that better meets their needs.”

The new rule “is primarily about increasing employer flexibility and worker choice of coverage,” said Brian Blase, special assistant to the president for health care policy. “We expect this rule to particularly benefit small employers and make it easier for them to compete with larger businesses by creating another option for financing worker health insurance coverage.”

The final rule is in response to the Trump administration’s October 2017 executive order on health care choice and competition, which resulted in an earlier final rule on association health plans that is now being challenged in the courts, and a final rule allowing low-cost short-term insurance that provides less coverage than a standard ACA plan.

New Types of HRAs

Existing HRAs are employer-funded accounts that employees can use to pay out-of-pocket health care expenses but may not use to pay insurance premiums. Unlike health savings accounts (HSAs), all HRAs, including the new ICHRA, are exclusively employer-funded, and, when employees leave the organization, their HRA funds go back to the employer. This differs from HSAs, which are employee-owned and portable when employees leave.

The proposed regulations keep the kinds of HRAs currently permitted (such as HRAs integrated with group health plans and retiree-only HRAs) and would recognize two new types of HRAs:

What ICHRAs Can Do

Under the new HRA rule:

The rule also includes a disclosure provision to help ensure that employees understand the type of HRA being offered by their employer and how the ICHRA offer may make them ineligible for a premium tax credit or subsidy when buying an ACA exchange-based plan. To help satisfy the notice requirements, the IRS issued an Individual Coverage HRA Model Notice.

QSEHRAs and ICHRAs

Currently, qualified small-employer HRAs (QSEHRAs), created by Congress in December 2016, allow small businesses with fewer than 50 full-time employees to use pretax dollars to reimburse employees who buy nongroup health coverage. The new rule goes farther and:

The legislation creating QSEHRAs set a maximum annual contribution limit with inflation-based adjustments. In 2019, annual employer contributions to QSEHRAs are capped at $5,150 for a single employee and $10,450 for an employee with a family.

The new rule, however, doesn’t cap contributions for ICHRAs.

As a result, employers with fewer than 50 full-time employees will have two choices—QSEHRAs or ICHRAs—with some regulatory differences between the two. For example:

“QSEHRAs have a special rule that allows employees to qualify for both their employer’s subsidy and the difference between that amount and any premium tax credit for which they’re eligible,” said John Barkett, director of policy affairs at consultancy Willis Towers Watson.

While the ability of employees to couple QSEHRAs with a premium tax credit is appealing, the downside is QSEHRA’s annual contribution limits, Barkett said. “QSEHRA’s are limited in their ability to fully subsidize coverage for older employees and employees with families, because employers could run through those caps fairly quickly,” he noted.

For older employees, the least expensive plan available on the individual market could easily cost $700 a month or $8,400 a year, Barkett pointed out, and “with a QSEHRA, an employer could only put in around $429 per month to stay under the $5,150 annual limit for self-only coverage.”

Similarly, for employees with many dependents, premiums could easily exceed the QSEHRA’s family coverage maximum of $10,450, whereas “all those dollars could be contributed pretax through an ICHRA,” Barkett said.

An Excepted-Benefit HRA

In addition to allowing ICHRAs, the final rule creates a new excepted-benefit HRA that lets employers that offer traditional group health plans provide an additional pretax $1,800 per year (indexed to inflation after 2020) to reimburse employees for certain qualified medical expenses, including premiums for vision, dental, and short-term, limited-duration insurance.

The new excepted-benefit HRAs can be used by employees whether or not they enroll in a traditional group health plan, and can be used to reimburse employees’ COBRA continuation coverage premiums and short-term insurance coverage plan premiums.

Safe Harbor Coming

With ICHRAs, employers still must satisfy the ACA’s affordability and minimum value requirements, just as they must do when offering a group health plan. However, “the IRS has signaled it will come out with a safe harbor that should make it straightforward for employers to determine whether their ICHRA offering would comply with ACA coverage requirements,” Barkett said.

Last year, the IRS issued Notice 2018-88, which outlined proposed safe harbor methods for determining whether individual coverage HRAs meet the ACA’s affordability threshold for employees, and which stated that ICHRAs that meet the affordability standard will be deemed to offer at least minimum value.

The IRS indicated that further rulemaking on these safe harbor methods is on its agenda for later this year.

The Trump administration announced a proposed rule today that would allow businesses to give employees money to purchase health insurance on the individual marketplace, a move senior officials say will expand choices for employees that work at small businesses.

The proposed rule, issued by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the Department of Labor (DOL) and the Department of Treasury, would restructure Obama-era regulations that limited the use of employer-funded accounts known as health reimbursement arrangements (HRA). The proposal is part of President Donald Trump’s “Promoting Healthcare Choice and Competition” executive order issued last year, which tasked the agencies with expanding the use of HRAs.

Senior administration officials said the proposed change would bring more competition to the individual marketplace by giving employees the chance to purchase health coverage on their own. The rule includes “carefully constructed guardrails” to prevent employers from keeping healthy employees on their company plans and incentivizing high-cost employees to seek coverage elsewhere.

That issue was a primary concern under the Obama administration, which barred the use of HRAs for premium assistance. The 21st Century Cures Act established Qualified Small Employer Health Reimbursement Accounts (QSEHRA), but those are subject to stringent limitations.

Under the new rule, HRA money would remain exempt from federal and payroll income taxes for employers and employees. Additionally, employers with traditional coverage would be permitted to reserve $1,800 for supplemental benefits like vision, dental and short-term health plans.

Officials estimate 10 million people would purchase insurance through HRAs, including 1 million people that were not previously insured. Most of those people would be concentrated in small and mid-sized businesses.

The proposed change would “unleash consumerism” and “spur innovation among providers and insurers that directly compete for consumer dollars,” one senior official said. Officials expect 7 million people will be added to the individual marketplace over the next 10 years.

The rule does not change the Affordable Care Act’s employer mandate, which requires employers with 50 or more employees to offer coverage to 95% of full-time employees. Administration officials expect the proposal will have the biggest impact on small businesses with less than 50 employees.

However, the rule could scale back the use of premium subsidies. If the HRA is considered “affordable” based on the amount provided by the employer, the employee would not be eligible for a premium tax credit. If the HRA fails to meet those minimum requirements, the employee could choose between a premium tax credit and the HRA.

Overall, the rule will “create a greater degree of value in healthcare and the health benefits marketplace than we would otherwise see,” one official said.

The regulation, if finalized, is proposed to be effective for plan years beginning on and after January 1, 2020.

Under the Affordable Care Act, (ACA) a fund for a new nonprofit corporation to assist in clinical effectiveness research was created. To aid in the financial support for this endeavor, certain health insurance carriers and health plan sponsors are required to pay fees based on the average number of lives covered by welfare benefits plans. These fees are referred to as either Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute (PCORI) or Clinical Effectiveness Research (CER) fees.

The applicable fee was $2.26 for plan years ending on or after October 1, 2016 and before October 1, 2017. For plan years ending on or after October 1, 2017 and before October 1, 2018, the fee is $2.39. Indexed each year, the fee amount is determined by the value of national health expenditures. The fee phases out and will not apply to plan years ending after September 30, 2019.

As a reminder, fees are required for all group health plans including Health Reimbursement Arrangements (HRAs), but are not required for health flexible spending accounts (FSAs) that are considered excepted benefits. To be an excepted benefit, health FSA participants must be eligible for their employer’s group health insurance plan and may include employer contributions in addition to employee salary reductions. However, the employer contributions may only be $500 per participant or up to a dollar for dollar match of each participant’s election.

HRAs exempt from other regulations would be subject to the CER fee. For instance, an HRA that only covered retirees would be subject to this fee, but those covering dental or vision expenses only would not be, nor would employee EAPs, disease management programs and wellness programs be required to pay CER fees.

Until very recently, employers were at risk of receiving steep fines if they reimbursed employees for non-employer sponsored medical care – the Affordable Care Act (ACA) included fines of up to $36,500 a year per employee for such an action. Late in 2016, however, President Obama signed the 21st Century Cures Act and established Qualified Small Employer Health Reimbursement Arrangements (QSEHRAs). As of January 1, 2017, small employers can offer these tax-free medical care reimbursements to eligible employees.

If an employee incurs a medical care expense, such as health insurance premiums or eligible medical expenses under IRC Section 213(d), the employer can reimburse the employee up to $4,950 for single coverage or $10,000 for family coverage. Employees may not make any contributions or salary deferrals to QSEHRAs.

The maximum amount must

be prorated for those not eligible for an entire year. For example, an employer

offering the maximum reimbursement amount should only reimburse up to $2,475 to

an employee who has been working for the company for six months. For a complete

list of medical expenses covered under IRC 213(d), see https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p502.pdf.

Employers may tailor which expenses they will reimburse to a certain extent,

and do not have to reimburse employees for all eligible medical expenses.

Much like other healthcare reimbursement arrangements, employees may have to provide substantiation before reimbursement. The IRS has discretion to establish requirements regarding this process, but has not yet done so. Although reimbursements may be provided tax-free, they must be reported on the employee’s W-2 in Box 12 using the code “FF.”

To offer QSEHRAs, an employer cannot be an applicable large employer (ALE) under the ACA. Only employers with fewer than 50 full-time equivalent employees can offer this benefit. Further, a group cannot offer group health plans to any employees to qualify.

Typically, an employer that chooses to offer a QSEHRA must offer it to all employees who have completed at least 90 days of work. The few exceptions to this rule include part-time or seasonal employees, non-resident aliens, employees under the age of 25, and employees covered by a collective bargaining agreement.

Employers may offer differing reimbursement amounts based on employee age or family size. However, such variances must be based on the cost of premiums of a reference policy on the individual market. It is currently unclear which reference policy will be selected or how permitted discrepancies will be calculated.

To be eligible for a tax-free reimbursement, employees must have proof of minimum essential coverage. It is uncertain how closely employers will have to scrutinize such proof, although guidance will hopefully be available soon.

Eligible employees must disclose to health exchanges the amount of QSEHRA benefits available to them. The exchanges will account for the reported amount, even if the employee does not utilize it, and will likely reduce the amount of the subsidies available. Employers should take this into account before adopting a QSEHRA.

In order to establish a QSEHRA, employers will have to set up and administer a plan. Group health plan requirements, such as ACA reporting and COBRA requirements, do not apply to QSEHRAs. But in order to properly provide reimbursements to employees, employers will likely have to establish reimbursement procedures.

Additionally, any eligible employees must be notified of the arrangements in writing at least 90 days before the first day they will be eligible to participate. For the current year, the IRS is giving employers who implement QSEHRAs an extension until March 13, 2017 to provide a notice. The notice must provide the amount of the maximum benefit, and that eligible employees inform health insurance exchanges this benefit is available to them. It also must inform eligible employees they may be subject to the individual ACA penalties if they do not have minimum essential coverage.

Earlier this week, President Obama signed the 21st Century Cures Act (“Act”). This Act contains provisions for “Qualified Small Business Health Reimbursement Arrangements” (“HRA”). This new HRA would allow eligible small employers to offer a health reimbursement arrangement funded solely by the employer that would reimburse employees for qualified medical expenses including health insurance premiums.

The maximum reimbursement that can be provided under the plan is $4,950 or $10,000 if the HRA provided for family members of the employee. An employer is eligible to establish a small employer health reimbursement arrangement if that employer (i) is not subject to the employer mandate under the Affordable Care Act (i.e., less than 50 full-time employees) and (ii) does not offer a group health plan to any employees.

To be a qualified small employer HRA, the arrangement must be provided on the same terms to all eligible employees, although the Act allows benefits under the HRA to vary based on age and family-size variations in the price of an insurance policy in the relevant individual health insurance market.

Employers must report contributions to a reimbursement arrangement on their employees’ W-2 each year and notify each participant of the amount of benefit provided under the HRA each year at least 90 days before the beginning of each year.

This new provision also provides that employees that are covered by this HRA will not be eligible for subsidies for health insurance purchased under an exchange during the months that they are covered by the employer’s HRA.

Such HRAs are not considered “group health plans” for most purposes under the Code, ERISA and the Public Health Service Act and are not subject to COBRA.

This new provision also overturns guidance issued by the Internal Revenue Service and the Department of Labor that stated that these arrangements violated the Affordable Care Act insurance market reforms and were subject to a penalty for providing such arrangements.

The previous IRS and DOL guidance would still prohibit these arrangements for larger employers. The provision is effective for plan years beginning after December 31, 2016. (There was transition relief for plans offering these benefits that ends December 31, 2016 and extends the relief given in IRS Notice 2015-17.)