Earlier this week, President Obama signed the 21st Century Cures Act (“Act”). This Act contains provisions for “Qualified Small Business Health Reimbursement Arrangements” (“HRA”). This new HRA would allow eligible small employers to offer a health reimbursement arrangement funded solely by the employer that would reimburse employees for qualified medical expenses including health insurance premiums.

The maximum reimbursement that can be provided under the plan is $4,950 or $10,000 if the HRA provided for family members of the employee. An employer is eligible to establish a small employer health reimbursement arrangement if that employer (i) is not subject to the employer mandate under the Affordable Care Act (i.e., less than 50 full-time employees) and (ii) does not offer a group health plan to any employees.

To be a qualified small employer HRA, the arrangement must be provided on the same terms to all eligible employees, although the Act allows benefits under the HRA to vary based on age and family-size variations in the price of an insurance policy in the relevant individual health insurance market.

Employers must report contributions to a reimbursement arrangement on their employees’ W-2 each year and notify each participant of the amount of benefit provided under the HRA each year at least 90 days before the beginning of each year.

This new provision also provides that employees that are covered by this HRA will not be eligible for subsidies for health insurance purchased under an exchange during the months that they are covered by the employer’s HRA.

Such HRAs are not considered “group health plans” for most purposes under the Code, ERISA and the Public Health Service Act and are not subject to COBRA.

This new provision also overturns guidance issued by the Internal Revenue Service and the Department of Labor that stated that these arrangements violated the Affordable Care Act insurance market reforms and were subject to a penalty for providing such arrangements.

The previous IRS and DOL guidance would still prohibit these arrangements for larger employers. The provision is effective for plan years beginning after December 31, 2016. (There was transition relief for plans offering these benefits that ends December 31, 2016 and extends the relief given in IRS Notice 2015-17.)

Rules Will Not Take Effect On December 1; Future Thereafter Uncertain

In a dramatic last-minute development, a federal judge in Texas on Tuesday (11/22/16) blocked the U.S. Department of Labor’s (DOL) overtime rule from taking effect on December 1. The judge issued a preliminary injunction preventing the rules from being implemented on a nationwide basis.

The fate of the overtime rules is now uncertain. The Trump administration will take over the DOL in less than two months’ time, and the incoming administration has repeatedly indicated that it wants to eliminate unnecessary regulations hampering the business community. Unless an appeals court reverses course in the next several weeks and breathes new life into the rules, it is quite possible that the rules will be further delayed, completely overhauled, or altogether scrapped once President Trump takes office.

Almost immediately, an outcry sprung from the business community, especially those advocating on behalf of small businesses. By doubling the existing salary threshold, the DOL’s actions would likely reduce the proportion of exempt workers sharply while increasing the compensation of many who will remain exempt, rather than engaging in the fundamentally definition process called for under the FLSA. As many pointed out, manipulating exemption requirements to “give employees a raise” has never been an authorized or legitimate pursuit.

Moreover, publishing what amounts to an automatic “update” to the minimum salary threshold is something that has never before happened in the more-than-75-year history of the FLSA exemptions. This departs from the prior DOL practice of engaging in what should instead ultimately be a qualitative evaluation that would take into account a variety of considerations.

The challengers argued that the DOL did not properly carry out its responsibility under the FLSA to define these exemptions, failing to take into account the duties of white-collar workers as the best indicator for whether threshold increases were needed. The plaintiffs also argued that the automatic indexing mechanism which would ratchet up the salary levels every three years was improper because it would ignore current economic conditions or the effect on public and private resources.

The judge recognized that, for 75 years, the salary levels that served as part of the DOL’s overtime exemption test acted as a floor and not a ceiling. He said during last week’s oral argument the new rule’s proposed salary jump was “a much more drastic change.” During that argument, in fact, he pointed out that the proposed substantial increase in the salary threshold could lead to inconsistent treatment of workers who each fulfill white collar duties but are paid differently. An example is a convenience store manager who clearly acts as an executive and who is paid a salary annualizing to only $47,000 a year, for example, would be treated differently than a similarly situated manager who is paid a salary equating to $47,500 a year.

Assuming that the injunction survives the remainder of President Obama’s term, it is difficult to predict what President Trump will do with the rules once in the White House. Perhaps President Trump will direct his DOL to commence a new rulemaking process, subject to notice and comment, with the goals of setting lower thresholds for the salary requirement and eliminating the three-year update, among other changes. How long and what form such a process would take, and what could or would be done in the meantime, are currently unpredictable.

At the same time, a series of measures have been introduced in Congress hoping to prevent or stall the rules changes. While one of the proposed legislative changes would scrap the increases altogether, another proposed change would delay implementation for a period of time to provide a longer period of preparation. Still, another would push the date that the full increase would take effect to 2019, introducing more forgiving gradual increases on an annual basis for the next three years.

The fate of these measures is similarly uncertain at present. Even if any of these measures were fast-tracked, approved by Congress, and signed by President Obama before he leaves office, it is unclear whether they would ever take effect given the nature of the current litigation.

If you had been waiting until December 1 to implement the changes, you have the option of putting any alterations on ice and awaiting a final determination on the fate of the rules. If you do so, you might consider communicating to your workforce that the expected changes are going to be delayed given today’s court ruling, and let them know that you will continue to monitor the situation and make adjustments when and if appropriate.

We will track these developments and provide updates as issued.

The Department of Justice released two new employee posters effective 8/1/16. Be sure to check your current postings and replace as needed. You can access the new posters below:

Employee Polygraph Protection Act Poster

Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) Minimum Wage Poster

Please contact our office if you have any questions.

The health reform law imposes a number of fees, taxes and other assessments on health insurance companies and sponsors of self-funded health plans to help subsidize a number of endeavors. One such fee funds the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI).

The PCORI fee is $2.17 per covered life for plan years ending on or after Oct. 1, 2015, and must be reported on (and remitted with) IRS Form 720 by Aug. 1, 2016 (the deadline is July 31, but since July 31 falls on a weekend, the form is due by the next business day, Aug. 1). For self-funded plans, the employer/plan sponsor will be responsible for submitting the fee and accompanying paperwork to the IRS. Third-party reporting and payment of the fee is not permitted for self-funded plans.

The process for remitting payment by sponsors of self-funded plans is described in more detail below.

The IRS will collect the fee from the insurer or, in the case of self-funded plans, the plan sponsor in the same way many other excise taxes are collected. The fees are reported and paid annually on IRS Form 720 by July 31 of the year following the last day of the plan year. This year the fee is due by Aug. 1.

The fee due on Aug. 1, 2016 is $2.17 per covered life for plan years ending before Oct. 1, 2016, and on or after Oct. 1, 2015. For plan years ending before Oct. 1, 2015, the fee due on Aug. 1, 2016, is $2.08 per covered life under the plan. IRS regulations provide three options for determining the average number of covered lives (actual count, snapshot and Form 5500 method).

The Form 720 must be filed by July 31 (Aug. 1 in 2016) of the calendar year immediately following the last day of the plan year. For example, calendar year plans will owe a fee of $2.17 per covered life by Aug. 1, 2016. Plans that operate on years that begin the first day of any month from February through October will be paying a $2.08 per covered life fee with the Aug. 1, 2016, filing.

The U.S. Department of Labor believes the fee cannot be paid from plan assets. In other words, the PCORI fee must be paid by the plan sponsor; it is not a permissible expense of a self-funded plan and cannot be paid in whole or part by participant contributions. The PCORI expense should not be included in the plan’s cost when computing the plan’s COBRA premium. The IRS has indicated the fee is, however, a tax-deductible business expense for employers with self-funded plans.

The filing and remittance process to the IRS is straightforward and is largely unchanged from last year. On page two of Form 720, under Part II, the employer needs to designate the average number of covered lives under its “applicable self-insured plan.” The number of covered lives is multiplied by $2.17 (for plan years ending on or after Oct. 1, 2015) to determine the total fee owed to the IRS.

The Payment Voucher (720-V) should indicate the tax period for the fee is “2nd Quarter.” Failure to properly designate “2nd Quarter” on the voucher will result in the IRS’s software generating a tardy filing notice, with all the incumbent aggravation on the employer to correct the matter with IRS.

The U.S Labor Department (USDOL) has finally released the anxiously awaited revised regulations affecting certain kinds of employees who may be treated as exempt from the federal Fair Labor Standards Act’s (FLSA) overtime and minimum-wage requirements. These will be published officially on May 23, 2016.

If you currently consider any of your employees to be exempt “white collar” employees, you might have to make some sweeping changes.

These rules will become effective on December 1, 2016, which is considerably later than had been thought. Unless this is postponed somehow, you must do by this time what is necessary to continue to rely upon one or more of these exemptions (or another exemption) as to each affected employee, or you must forgo exempt status as to any employee who no longer satisfies all of the requirements.

Essentially, USDOL is doubling the current salary threshold. This is likely intended to both reduce the proportion of exempt workers sharply while increasing the compensation of many who will remain exempt, rather than engaging in the fundamentally definition process called for under the FLSA. Manipulating exemption requirements to “give employees a raise” has never been an authorized or legitimate pursuit.

For the first time in the exemptions’ more-than-75-year history, USDOL will publish what amounts to an automatic “update” to the minimum salary threshold. This departs from the prior USDOL practice of engaging in what should instead ultimately be a qualitative evaluation that also takes into account a variety of non-numerical considerations.

USDOL did not change any of the exemptions’ requirements as they relate to the kinds or amounts of work necessary to sustain exempt status (commonly known as the “duties test”). Of course, USDOL had asked for comments directed to whether there should be a strict more-than-50% requirement for exempt work. The agency apparently decided that this was not necessary in light of the fact that “the number of workers for whom employers must apply the duties test is reduced” by virtue of the salary increase alone.

Right now, you should be:

USDOL has provided extensive commentary explaining its rationale for the revised provisions. We are continuing to study the final regulations and accompanying discussion carefully and will provide updates/changes as published.

In late April, the Department of Labor (DOL) announced that it soon will issue a new general FMLA Notice that can be used interchangeably with their current FMLA posting. In issuing this new directive, they also unveiled a new guide to help employers navigate and administer the FMLA.

Here’s the scoop:

Under the FMLA, an FMLA-covered employer must post a copy of the General FMLA Notice in each location where it has any employees (even if there are no FMLA-eligible employees at that location). According to the FMLA rules, the notice must be posted “prominently where it can be readily seen by employees and applicants for employment.”

The DOL has announced that it will release a new General FMLA Notice for employers to post in their workplaces. According to the DOL, the new poster won’t necessarily include a whole bunch of new information. Rather, the information in the notice will be reorganized so that it’s more reader friendly.

The DOL’s Branch Chief for FMLA, Helen Applewhaite, confirmed that employers would be allowed to post either the current poster or the new version. In other words, employers will not be required to change the current poster.

In 2012, the DOL issued a guide to employees to help them navigate their rights under the FMLA. Several years later, DOL now has issued a companion guide for employers. According to the DOL, the Employer’s Guide to the Family and Medical Leave Act (pdf) is designed to “provide essential information about the FMLA, including information about employers’ obligations under the law and the options available to employers in administering leave under the FMLA.”

The new guide was unveiled by the DOL at an annual FMLA/ADA Compliance conference sponsored by the Disability Management Employer Coalition (DMEC). Generally speaking, the new guide covers FMLA administration from beginning to end, and it follows a typical leave process — from leave request through medical certification and return to work.

While the guide helps explain the FMLA regulations in a user-friendly manner, the guide primarily is meant to answer common questions about the FMLA, so it leaves unanswered leave issues that continue to frustrate employers in their administration of the FMLA. However, the guide is likely to have some benefit to employers when administering the FMLA. For instance, the guide:

After more than 15 months of waiting, the U.S. Department of Labor has issued a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (“NPRM”) announcing the Department’s intention to shrink dramatically the pool of employees who qualify for exempt status under the Fair Labor Standards Act.

The 295-page NPRM, released June 30, contains a few specific changes to existing DOL regulations: more than doubling the salary threshold for the executive, administrative, and professional exemptions from $455 a week currently to $921 a week (with a plan to increase that number to $970 a week in the final version of the regulation), as well as raising the pay thresholds for certain other exemptions, and building in room for future annual increases. More ominously, the Department invites comment on a host of other issues. This opens the door to many further significant revisions to the regulations in a Final Rule after the Department reviews the public’s comments to the NPRM.

Background

On March 13, 2014, President Obama directed the Secretary of Labor to modernize and streamline the existing overtime regulations for exempt executive, administrative, and professional employees. He said the compensation paid to these employees has not kept pace with America’s economy since the Department last revised regulations in 2004. The President noted that the minimum annual salary level for these exempt classifications under the 2004 regulations is $23,660, which is below the poverty line for a family of four.

Since the President issued his memo, the Department has held meetings with a variety of stakeholders, including employers, workers, trade associations, and other advocates. The Department has raised questions about how the current regulations work and how they can be improved. The discussions have focused on the compensation levels for the exempt classifications as well as the duties required to qualify for exempt status.

The NPRM

The NPRM expressed the Department’s intention to increase the salary threshold for the white-collar exemptions from $455 a week (or $23,660 a year) to $921 a week ($47,892 a year), which the Department expects to revise to $970 a week ($50,440 a year in 2016) when it issues its Final Rule. Under this single change to the regulations, it is estimated that 4.6 million currently exempt employees would lose their exemption right away, with another 500,000 to 1 million currently exempt employees losing exempt status over the next 10 years as a result of the automatic increases to the salary threshold.

The NPRM acknowledges that roughly 25% of all employees currently exempt and subject to the salary basis requirement will be rendered non-exempt under the proposed regs. The Department recognizes that employers are likely to reduce the working hours of currently exempt employees reclassified as a result of these regulations, and that the reduction in hours will probably lead to lower overall pay for these employees.

Related changes in the regs include increasing the annual compensation threshold for exempt highly compensated employees from the present level of $100,000 to a proposed $122,148, as well as raising the exemption threshold for the motion picture producing industry from the present $695 a week to a proposed $1,404 a week for employees compensated on a day-rate basis.

Perhaps not surprisingly, given the likely impact of the proposal, almost all of the NPRM is devoted to economic analysis and justification for the steep increase in the salary thresholds. Nevertheless, the NPRM touches on some other topics as well. The Department states that it is considering, and invites comment on, a wide range of topics, including:

What Comes Next?

The proposed regulations are subject to a 30-day public comment period. Now is the time for any employer or trade association dissatisfied with the proposed regulatory text, or concerned about changes the Department is weighing for inclusion in a Final Rule, to submit comments. The Department has put the regulated public on notice: it is considering sweeping changes to the regulations not described specifically in the proposed regulatory text, such as altering the duties tests for exempt status. Employers may not have another opportunity to comment on the content of a Final Rule.

Following the public comment period, the Department will issue a Final Rule that may add, change, delete, or affirm the regulatory text of the proposal. The Office of Management and Budget will review the Final Rule before publication. This process is likely to take at least six to eight months. A Final Rule is not expected before 2016.

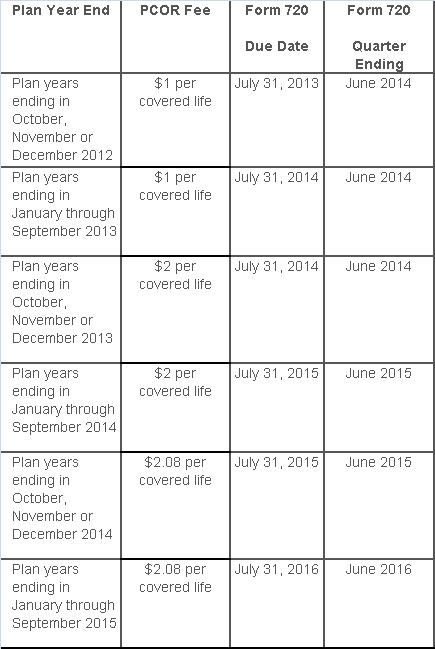

The Affordable Care Act added a patient-centered outcomes research (PCOR) fee on health plans to support clinical effectiveness research. The PCOR fee applies to plan years ending on or after Oct. 1, 2012, and before Oct. 1, 2019. The PCOR fee is due by July 31 of the calendar year following the close of the plan year. For plan years ending in 2014, the fee is due by July 31, 2015.

PCOR fees are required to be reported annually on Form 720, Quarterly Federal Excise Tax Return, for the second quarter of the calendar year. The due date of the return is July 31. Plan sponsors and insurers subject to PCOR fees but not other types of excise taxes should file Form 720 only for the second quarter, and no filings are needed for the other quarters. The PCOR fee can be paid electronically or mailed to the IRS with the Form 720 using a Form 720-V payment voucher for the second quarter. According to the IRS, the fee is tax-deductible as a business expense.

The PCOR fee is assessed based on the number of employees, spouses and dependents that are covered by the plan. The fee is $1 per covered life for plan years ending before Oct. 1, 2013, and $2 per covered life thereafter, subject to adjustment by the government. For plan years ending between Oct. 1, 2014, and Sept. 30, 2015, the fee is $2.08. The Form 720 instructions are expected to be updated soon to reflect this increased fee.

This chart summarizes the fee schedule based on the plan year end and shows the Form 720 due date. It also contains the quarter ending date that should be reported on the first page of the Form 720 (month and year only per IRS instructions). The plan year end date is not reported on the Form 720.

For insured plans, the insurance company is responsible for filing Form 720 and paying the PCOR fee. Therefore, employers with only fully- insured health plans have no filing requirement.

If an employer sponsors a self-insured health plan, the employer must file Form 720 and pay the PCOR fee. For self-insured plans with multiple employers, the named plan sponsor is generally required to file Form 720. A self-insured health plan is any plan providing accident or health coverage if any portion of such coverage is provided other than through an insurance policy.

Since the fee is a tax assessed against the plan sponsor and not the plan, most funded plans subject to ERISA must not pay the fee using plan assets since doing so would be considered a prohibited transaction by the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL). The DOL has provided some limited exceptions to this rule for plans with multiple employers if the plan sponsor exists solely for the purpose of sponsoring and administering the plan and has no source of funding independent of plan assets.

Plans sponsored by all types of employers, including tax-exempt organizations and governmental entities, are subject to the PCOR fee. Most health plans, including major medical plans, prescription drug plans and retiree-only plans, are subject to the PCOR fee, regardless of the number of plan participants. The special rules that apply to Health Reimbursement Accounts (HRAs) and Health Flexible Spending Accounts (FSAs) are discussed below.

Plans exempt from the fee include:

If a plan sponsor maintains more than one self-insured plan, the plans can be treated as a single plan if they have the same plan year. For example, if an employer has a self-insured medical plan and a separate self-insured prescription drug plan with the same plan year, each employee, spouse and dependent covered under both plans is only counted once for purposes of the PCOR fee.

The IRS has created a helpful chart showing how the PCOR fee applies to common types of health plans.

Health Reimbursement Accounts (HRAs) - Nearly all HRAs are subject to the PCOR fee because they do not meet the conditions for exemption. An HRA will be exempt from the PCOR fee if it provides benefits only for dental or vision expenses, or it meets the following three conditions:

Health Flexible Spending Accounts (FSAs) - A health FSA is exempt from the PCOR fee if it satisfies an availability condition and a maximum benefit condition.

Additional special rules for HRAs and FSAs . Once an employer determines that its HRA or FSA is subject to the PCOR fee, the employer should consider the following special rules:

The IRS provides different rules for determining the average number of covered lives (i.e., employees, spouses and dependents) under insured plans versus self-insured plans. The same method must be used consistently for the duration of any policy or plan year. However, the insurer or sponsor is not required to use the same method from one year to the next.

A plan sponsor of a self-insured plan may use any of the following three

methods to determine the number of covered lives for a plan year:

1. Actual count method. Count the covered lives on each day of the plan year and divide by the number of days in the plan year.

Example: An employer has 900 covered lives on Jan. 1, 901 on Jan. 2, 890 on

Jan. 3, etc., and the sum of the lives covered under the plan on each day of

the plan year is 328,500. The average number of covered lives is 900 (328,500 ÷

365 days).

2. Snapshot method. Count the covered lives on a single day in each quarter (or more than one day) and divide the total by the number of dates on which a count was made. The date or dates must be consistent for each quarter. For example, if the last day of the first quarter is chosen, then the last day of the second, third and fourth quarters should be used as well.

Example: An employer has 900 covered lives on Jan. 15, 910 on April 15, 890 on

July 15, and 880 on Oct. 15. The average number of covered lives is 895 [(900 +

910+ 890+ 880) ÷ 4 days].

As an alternative to counting actual lives, an employer can count the number of

employees with self-only coverage on the designated dates, plus the number of

employees with other than self-only coverage multiplied by 2.35.

3. Form 5500 method. If a Form 5500 for a plan is filed before the due date of the Form 720 for that year, the plan sponsor can determine the number of covered lives based on the Form 5500. If the plan offers just self-only coverage, the plan sponsor adds the participant counts at the beginning and end of the year (lines 5 and 6d on Form 5500) and divides by 2. If the plan also offers family or dependent coverage, the plan sponsor adds the participant counts at the beginning and end of the year (lines 5 and 6d on Form 5500) without dividing by 2.

Example: An employer offers single and family coverage with a plan year ending

on Dec. 31. The 2013 Form 5500 is filed on June 5, 2014, and reports 132

participants on line 5 and 148 participants on line 6d. The number of covered

lives is 280 (132 + 148).

To evaluate liability for PCOR fees, plan sponsors should identify all of their plans that provide medical benefits and determine if each plan is insured or self-insured. If any plan is self-insured, the plan sponsor should take the following actions:

While the rest of us were enjoying our Memorial Day holiday, the Department of Labor was busy posting the new model FMLA notices and medical certification forms… with an expiration date of May 31, 2018!

No more month-to-month extensions or lost sleep over when the long-awaited forms would be released.

That said, it couldn’t have taken DOL a whole lot of time to draft the updated forms. After a relatively close review of the new forms, the notable change is a reference to the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA). In the instructions to the health care provider on the certification for an employee’s serious health condition, the DOL has added the following simple instruction:

Do not provide information about genetic tests, as defined in 29 C.F.R. § 1635.3(f), genetic services, as defined in 29 C.F.R. § 1635.3(e), or the manifestation of disease or disorder in the employee’s family members, 29 C.F.R. § 1635.3(b).

The DOL added similar language to the other medical certification forms as well. For years, employers have included GINA disclaimers in their FMLA paperwork, and those disclaimers typically have been far more robust (and reader-friendly) than the cryptic one the DOL used above.

For easy reference, here are the links to the new FMLA forms:

The forms also can be accessed from this DOL web page.

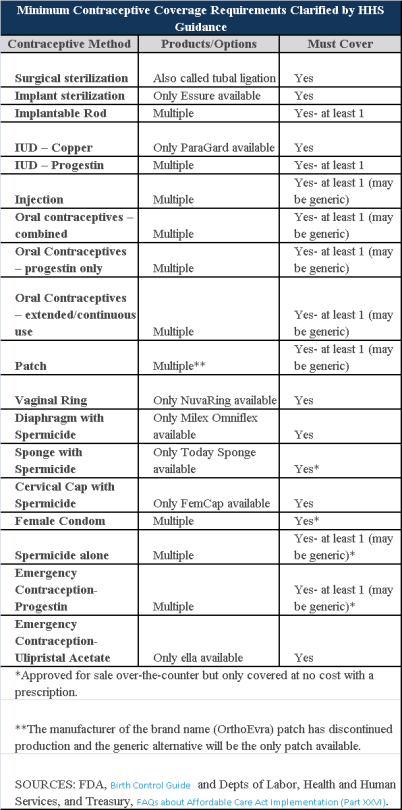

Plans and insurers must cover all 18 contraception methods approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, according to a new set of questions and answers on the Affordable Care Act’s preventive care coverage requirements.

“Reasonable medical management” still may be used to steer members to specific products within those methods of contraception. A plan or insurer may impose cost-sharing on non-preferred items within a given method, as long as at least one form of contraception in each method is covered without cost-sharing.

However, an individual’s physician must be allowed to override the plan’s drug management techniques if the physician finds it medically necessary to cover without cost-sharing an item that a given plan or insurer has classified as non-preferred, according to one of the frequently asked questions from the U.S. Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services and the Treasury.

The ACA mandated all plans and insurers to cover preventive care items, as defined by the Public Health Service Act, without cost-sharing. Eighteen forms of female contraception are included under the preventive care list. The individual FAQs on contraception clarified the following requirements.

The FAQ comes just weeks after reports and news coverage detailed health plan violations of the women coverage provisions of the ACA.

Testing and Dependent Care Answers

In questions separate from contraception, plans and insurers were told they must cover breast cancer susceptibility (BRCA-1 or BRCA-2) testing without cost-sharing. The test identifies whether the woman has genetic mutations that make her more susceptible to BRCA-related breast cancer.

Another question stated that if colonoscopies are performed as preventive screening without cost-sharing, then plans could not impose cost-sharing on the anesthesia component of that service.