After more than 15 months of waiting, the U.S. Department of Labor has issued a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (“NPRM”) announcing the Department’s intention to shrink dramatically the pool of employees who qualify for exempt status under the Fair Labor Standards Act.

The 295-page NPRM, released June 30, contains a few specific changes to existing DOL regulations: more than doubling the salary threshold for the executive, administrative, and professional exemptions from $455 a week currently to $921 a week (with a plan to increase that number to $970 a week in the final version of the regulation), as well as raising the pay thresholds for certain other exemptions, and building in room for future annual increases. More ominously, the Department invites comment on a host of other issues. This opens the door to many further significant revisions to the regulations in a Final Rule after the Department reviews the public’s comments to the NPRM.

Background

On March 13, 2014, President Obama directed the Secretary of Labor to modernize and streamline the existing overtime regulations for exempt executive, administrative, and professional employees. He said the compensation paid to these employees has not kept pace with America’s economy since the Department last revised regulations in 2004. The President noted that the minimum annual salary level for these exempt classifications under the 2004 regulations is $23,660, which is below the poverty line for a family of four.

Since the President issued his memo, the Department has held meetings with a variety of stakeholders, including employers, workers, trade associations, and other advocates. The Department has raised questions about how the current regulations work and how they can be improved. The discussions have focused on the compensation levels for the exempt classifications as well as the duties required to qualify for exempt status.

The NPRM

The NPRM expressed the Department’s intention to increase the salary threshold for the white-collar exemptions from $455 a week (or $23,660 a year) to $921 a week ($47,892 a year), which the Department expects to revise to $970 a week ($50,440 a year in 2016) when it issues its Final Rule. Under this single change to the regulations, it is estimated that 4.6 million currently exempt employees would lose their exemption right away, with another 500,000 to 1 million currently exempt employees losing exempt status over the next 10 years as a result of the automatic increases to the salary threshold.

The NPRM acknowledges that roughly 25% of all employees currently exempt and subject to the salary basis requirement will be rendered non-exempt under the proposed regs. The Department recognizes that employers are likely to reduce the working hours of currently exempt employees reclassified as a result of these regulations, and that the reduction in hours will probably lead to lower overall pay for these employees.

Related changes in the regs include increasing the annual compensation threshold for exempt highly compensated employees from the present level of $100,000 to a proposed $122,148, as well as raising the exemption threshold for the motion picture producing industry from the present $695 a week to a proposed $1,404 a week for employees compensated on a day-rate basis.

Perhaps not surprisingly, given the likely impact of the proposal, almost all of the NPRM is devoted to economic analysis and justification for the steep increase in the salary thresholds. Nevertheless, the NPRM touches on some other topics as well. The Department states that it is considering, and invites comment on, a wide range of topics, including:

What Comes Next?

The proposed regulations are subject to a 30-day public comment period. Now is the time for any employer or trade association dissatisfied with the proposed regulatory text, or concerned about changes the Department is weighing for inclusion in a Final Rule, to submit comments. The Department has put the regulated public on notice: it is considering sweeping changes to the regulations not described specifically in the proposed regulatory text, such as altering the duties tests for exempt status. Employers may not have another opportunity to comment on the content of a Final Rule.

Following the public comment period, the Department will issue a Final Rule that may add, change, delete, or affirm the regulatory text of the proposal. The Office of Management and Budget will review the Final Rule before publication. This process is likely to take at least six to eight months. A Final Rule is not expected before 2016.

The Supreme Court left one of its most high-profile decisions for the end of its term, holding today by a 5-4 vote that the Constitution requires states to recognize same-sex marriage. As a result, state bans against same-sex marriage are no longer permissible and all states are required to recognize same-sex marriages that take place in other states. Employers should update their FMLA policies and benefit plans to provide the same coverage for same-sex married couples as for other married couples. Obergefell v. Hodges.

Background

In 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Section 3 of the Federal Defense of

Marriage Act (DOMA), which essentially barred same-sex married couples from

being recognized as “spouses” for purposes of federal laws, violated the Fifth

Amendment (United States v.

Windsor). On the heels of that case, same-sex couples sued their

relevant state agencies in Ohio, Michigan, Kentucky, and Tennessee to challenge

the constitutionality of those states’ same-sex marriage bans, as well as their

refusal to recognize legal same-sex marriages that occurred in other

jurisdictions.

For instance, the named plaintiff, James Obergefell, married a man named John Arthur in Maryland. Arthur died a few months later in Ohio where the couple lived, but Obergefell did not appear on his death certificate as his “spouse” because Ohio does not recognize same-sex marriage. Similarly, Army Reserve Sergeant First Class Ijpe DeKoe married Thomas Kostura in New York, which permits same-sex marriage. When Sgt. DeKoe returned from Afghanistan, the couple moved to Tennessee, but that state refused to recognize their marriage.

The plaintiffs in each case argued that the states’ refusal to recognize their same-sex marriages violated the Equal Protection Clause and Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. In all the cases, the trial court found in favor of the plaintiffs. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit reversed and held that states’ bans on same-sex marriage and refusal to recognize marriages performed in other states did not violate Fourteenth Amendment rights to equal protection and due process.

The Supreme Court accepted review of the controversy, focusing its analysis on whether the Constitution requires all states to recognize same-sex marriage, and whether it requires a state which refuses to recognize same-sex marriage to nevertheless recognize same-sex marriages entered into in other states where such unions are permitted.

Same-Sex

Marriage Is Guaranteed By The Constitution

In its ruling today, the Supreme Court sided with the plaintiffs and held that

marriage is a fundamental right; as such, same-sex couples cannot be deprived

of that right pursuant to the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

Practical

Impact On Employers: FMLA Policies and Benefit Documents Must Be Updated

Following Windsor, the Department of

Labor issued a Final Rule revising FMLA’s definition of “spouse” to ensure that

same-sex married couples receive FMLA rights and protections without regard to

where they reside. Specifically, the DOL’s Final Rule adopts a “place of

celebration” rule, meaning that when defining a spouse under the FMLA, it

refers “to the other person with whom an individual entered into marriage as

defined or recognized under state law for purposes of marriage in the State in

which the marriage was entered into or, in the case of a marriage entered into

outside of any State, if the marriage is valid in the place where entered into

and could have been entered into in at least one State.” In other words, this

broad interpretation was intended to ensure that FMLA coverage existed for

same-sex couples even in states where same-sex marriage was banned.

The Final Rule had been temporarily enjoined in Texas, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Nebraska by a federal judge who ruled that the DOL did not have the authority to change the definition of “spouse,” and that the change “improperly preempts state law forbidding the recognition of same-sex marriages for the purpose of state-given benefits.” That litigation was on hold pending the outcome of this case. The Supreme Court’s decision in Obergefell paves the way for the Final Rule to go into effect, which means that employers should update their FMLA policies accordingly.

Additionally, employers should review their benefit offerings and consider the impact this decision has on employees who are in same-sex marriages.

Ironically, the Obergefell decision does not change the fact that sexual orientation is still not a protected class under federal law for employment law purposes. Although many states and municipalities protect against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, the proposed amendment to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 remains in limbo.

In a 6-3 decision handed down June 25th by the U.S. Supreme Court, the IRS was authorized to issue regulations extending health insurance subsidies to coverage purchased through health insurance exchanges run by the federal government or a state (King v. Burwell, No. 14-114 ).

This means employers cannot avoid employer shared responsibility penalties under IRC section 4980H (“Code § 4980H”) with respect to an employee solely because the employee obtained subsidized exchange coverage in a state that has a health insurance exchange set up by the federal government instead of by the state. It also means that President Barack Obama’s 2010 health care reform law will not be unraveled by the Supreme Court’s decision in this case. The law’s requirements applicable to employers and group health plans continue to apply without change.

What Was the Case About?

IRC section 36B (“Code § 36B”), created by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (“ACA”), provides that an individual who buys health insurance “through an Exchange established by the State under section 1311 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act” (emphasis added) generally is entitled to subsidies unless the individual’s income is too high. Thus, the words of the statute conditioned one’s right to an exchange subsidy on one’s purchase of ACA coverage in a state run exchange.

Since 2014, an individual who fails to maintain health insurance for any month generally is subject to a tax penalty unless the individual can show that no affordable coverage was available. The law defines affordability for this purpose in such a way that, without a subsidy, health insurance would be unaffordable for most people.

The plaintiffs in King, residents of one of the 34 states that did not establish a state run health insurance exchange argued that if subsidies were not available to them, no health insurance coverage would be affordable for them and they would not be required to pay a penalty for failing to maintain health insurance. The IRS, however, made subsidized federal exchange coverage available to them similar to coverage in a state run exchange.

It is ACA § 1311 that established the funding and other incentives for “the States” to each establish a state-run exchange through which residents of the state could buy health insurance. Section 1311 also provides that the Secretary of the Treasury will appropriate funds to “make available to each State” and that the “State shall use amounts awarded for activities (including planning activities) related to establishing an American Health Benefit Exchange.” Section 1311 describes an “American Health Benefit Exchange” as follows:

Each State shall, not later than January 1, 2014, establish an American Health Benefit Exchange (referred to in this title as an “Exchange”) for the State that (A) facilitates the purchase of qualified health plans; (B) provides for the establishment of a Small Business Health Options Program and © meets [specific requirements enumerated].

An entirely separate section of the ACA provides for the establishment of a federally-run exchange for individuals to buy health insurance if they reside in a state that does not establish a 1311 exchange. That section – ACA § 1321 – withholds funding from a state that has failed to establish a 1311 exchange.

Notwithstanding the statutory language Congress used in the ACA (i.e., literally conditioning an individual’s eligibility subsidized exchange coverage on the purchase of health insurance through a state’s 1311 exchange), the Supreme Court determined that the language is ambiguous. Having found that the text is ambiguous, the Court stated that it must determine what Congress really meant by considering the language in context and with a view to the placement of the words in the overall statutory scheme.

When viewed in this context, the Court concluded that the plain language could not be what Congress actually meant, as such interpretation would destabilize the individual insurance market in those states with a federal exchange and likely create the “death spirals” the ACA was designed to avoid. The Court reasoned that Congress could not have intended to delegate to the IRS the authority to determine whether subsidies would be available only on state run exchanges because the issue is of such deep economic and political significance. The Court further noted that “had Congress wished to assign that question to an agency, it surely would have done so expressly” and “[i]t is especially unlikely that Congress would have delegated this decision to the IRS, which has no expertise in crafting health insurance policy of this sort.”

What Now?

Regardless of whether one agrees with the Supreme Court’s King decision, the decision prevents any practical purpose for further discussion about whether the IRS had authority to extend taxpayer subsidies to individuals who buy health insurance coverage on federal exchanges.

The ACA’s next major compliance requirements for employers: Employers with fifty or more fulltime and fulltime equivalent employees need to ensure that they are tracking hours of service and are otherwise prepared to meet the large employer reporting requirements for 2015 (due in early 2016) ). Employers of any size that sponsor self-funded group health plans need to ensure that they are prepared to meet the health plan reporting requirements for 2015 (also due in early 2016). All employers that sponsor group health plans also should be considering whether and to what extent the so-called Cadillac tax could apply beginning in 2018.

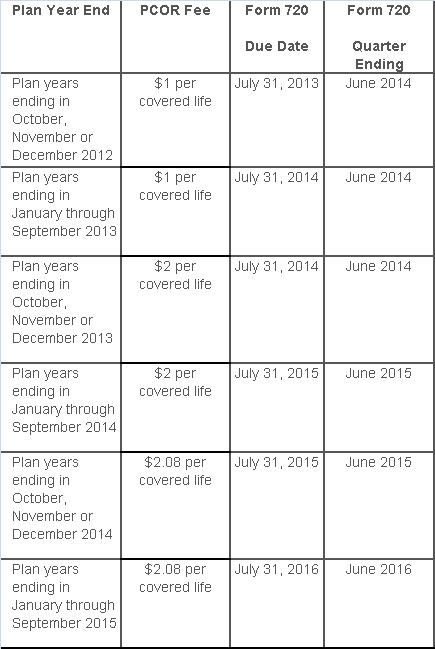

The Affordable Care Act added a patient-centered outcomes research (PCOR) fee on health plans to support clinical effectiveness research. The PCOR fee applies to plan years ending on or after Oct. 1, 2012, and before Oct. 1, 2019. The PCOR fee is due by July 31 of the calendar year following the close of the plan year. For plan years ending in 2014, the fee is due by July 31, 2015.

PCOR fees are required to be reported annually on Form 720, Quarterly Federal Excise Tax Return, for the second quarter of the calendar year. The due date of the return is July 31. Plan sponsors and insurers subject to PCOR fees but not other types of excise taxes should file Form 720 only for the second quarter, and no filings are needed for the other quarters. The PCOR fee can be paid electronically or mailed to the IRS with the Form 720 using a Form 720-V payment voucher for the second quarter. According to the IRS, the fee is tax-deductible as a business expense.

The PCOR fee is assessed based on the number of employees, spouses and dependents that are covered by the plan. The fee is $1 per covered life for plan years ending before Oct. 1, 2013, and $2 per covered life thereafter, subject to adjustment by the government. For plan years ending between Oct. 1, 2014, and Sept. 30, 2015, the fee is $2.08. The Form 720 instructions are expected to be updated soon to reflect this increased fee.

This chart summarizes the fee schedule based on the plan year end and shows the Form 720 due date. It also contains the quarter ending date that should be reported on the first page of the Form 720 (month and year only per IRS instructions). The plan year end date is not reported on the Form 720.

For insured plans, the insurance company is responsible for filing Form 720 and paying the PCOR fee. Therefore, employers with only fully- insured health plans have no filing requirement.

If an employer sponsors a self-insured health plan, the employer must file Form 720 and pay the PCOR fee. For self-insured plans with multiple employers, the named plan sponsor is generally required to file Form 720. A self-insured health plan is any plan providing accident or health coverage if any portion of such coverage is provided other than through an insurance policy.

Since the fee is a tax assessed against the plan sponsor and not the plan, most funded plans subject to ERISA must not pay the fee using plan assets since doing so would be considered a prohibited transaction by the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL). The DOL has provided some limited exceptions to this rule for plans with multiple employers if the plan sponsor exists solely for the purpose of sponsoring and administering the plan and has no source of funding independent of plan assets.

Plans sponsored by all types of employers, including tax-exempt organizations and governmental entities, are subject to the PCOR fee. Most health plans, including major medical plans, prescription drug plans and retiree-only plans, are subject to the PCOR fee, regardless of the number of plan participants. The special rules that apply to Health Reimbursement Accounts (HRAs) and Health Flexible Spending Accounts (FSAs) are discussed below.

Plans exempt from the fee include:

If a plan sponsor maintains more than one self-insured plan, the plans can be treated as a single plan if they have the same plan year. For example, if an employer has a self-insured medical plan and a separate self-insured prescription drug plan with the same plan year, each employee, spouse and dependent covered under both plans is only counted once for purposes of the PCOR fee.

The IRS has created a helpful chart showing how the PCOR fee applies to common types of health plans.

Health Reimbursement Accounts (HRAs) - Nearly all HRAs are subject to the PCOR fee because they do not meet the conditions for exemption. An HRA will be exempt from the PCOR fee if it provides benefits only for dental or vision expenses, or it meets the following three conditions:

Health Flexible Spending Accounts (FSAs) - A health FSA is exempt from the PCOR fee if it satisfies an availability condition and a maximum benefit condition.

Additional special rules for HRAs and FSAs . Once an employer determines that its HRA or FSA is subject to the PCOR fee, the employer should consider the following special rules:

The IRS provides different rules for determining the average number of covered lives (i.e., employees, spouses and dependents) under insured plans versus self-insured plans. The same method must be used consistently for the duration of any policy or plan year. However, the insurer or sponsor is not required to use the same method from one year to the next.

A plan sponsor of a self-insured plan may use any of the following three

methods to determine the number of covered lives for a plan year:

1. Actual count method. Count the covered lives on each day of the plan year and divide by the number of days in the plan year.

Example: An employer has 900 covered lives on Jan. 1, 901 on Jan. 2, 890 on

Jan. 3, etc., and the sum of the lives covered under the plan on each day of

the plan year is 328,500. The average number of covered lives is 900 (328,500 ÷

365 days).

2. Snapshot method. Count the covered lives on a single day in each quarter (or more than one day) and divide the total by the number of dates on which a count was made. The date or dates must be consistent for each quarter. For example, if the last day of the first quarter is chosen, then the last day of the second, third and fourth quarters should be used as well.

Example: An employer has 900 covered lives on Jan. 15, 910 on April 15, 890 on

July 15, and 880 on Oct. 15. The average number of covered lives is 895 [(900 +

910+ 890+ 880) ÷ 4 days].

As an alternative to counting actual lives, an employer can count the number of

employees with self-only coverage on the designated dates, plus the number of

employees with other than self-only coverage multiplied by 2.35.

3. Form 5500 method. If a Form 5500 for a plan is filed before the due date of the Form 720 for that year, the plan sponsor can determine the number of covered lives based on the Form 5500. If the plan offers just self-only coverage, the plan sponsor adds the participant counts at the beginning and end of the year (lines 5 and 6d on Form 5500) and divides by 2. If the plan also offers family or dependent coverage, the plan sponsor adds the participant counts at the beginning and end of the year (lines 5 and 6d on Form 5500) without dividing by 2.

Example: An employer offers single and family coverage with a plan year ending

on Dec. 31. The 2013 Form 5500 is filed on June 5, 2014, and reports 132

participants on line 5 and 148 participants on line 6d. The number of covered

lives is 280 (132 + 148).

To evaluate liability for PCOR fees, plan sponsors should identify all of their plans that provide medical benefits and determine if each plan is insured or self-insured. If any plan is self-insured, the plan sponsor should take the following actions:

While the rest of us were enjoying our Memorial Day holiday, the Department of Labor was busy posting the new model FMLA notices and medical certification forms… with an expiration date of May 31, 2018!

No more month-to-month extensions or lost sleep over when the long-awaited forms would be released.

That said, it couldn’t have taken DOL a whole lot of time to draft the updated forms. After a relatively close review of the new forms, the notable change is a reference to the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA). In the instructions to the health care provider on the certification for an employee’s serious health condition, the DOL has added the following simple instruction:

Do not provide information about genetic tests, as defined in 29 C.F.R. § 1635.3(f), genetic services, as defined in 29 C.F.R. § 1635.3(e), or the manifestation of disease or disorder in the employee’s family members, 29 C.F.R. § 1635.3(b).

The DOL added similar language to the other medical certification forms as well. For years, employers have included GINA disclaimers in their FMLA paperwork, and those disclaimers typically have been far more robust (and reader-friendly) than the cryptic one the DOL used above.

For easy reference, here are the links to the new FMLA forms:

The forms also can be accessed from this DOL web page.

According to recent news reports, nearly half of the 17 Exchanges run by states and the District of Columbia under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) are struggling financially:

Many of the online exchanges are wrestling with surging costs, especially for balky technology and expensive customer call centers — and tepid enrollment numbers. To ease the fiscal distress, officials are considering raising fees on insurers, sharing costs with other states and pressing state lawmakers for cash infusions. Some are weighing turning over part or all of their troubled marketplaces to the federal exchange, HealthCare.gov, which now works smoothly.

Of course, many states can’t solve their financial troubles easily. As independent entities, their income depends on fees imposed on insurers, which is then often passed on to the consumer signing up for health care. However, those fees are entirely contingent on how many people enroll in that particular Exchange; low enrollment invariably means higher costs.

Low enrollment is where the trouble thickens. The recently completed open enrollment period only rose 12 percent to 2.8 million sign-ups for state Exchanges, according to The Washington Post. Comparatively, the federal Exchange saw an increase of 61 percent to 8.8 million people.

According to the Post, state Exchanges have operating budgets between “$28 million and $32 million”. Most of the money tends to go to call centers, “Enrollment can be a lengthy process — and in several states, contractors are paid by the minute. An even bigger cost involves IT work to correct defective software that might, for example, make mistakes in calculating subsidies.”

However, The Fiscal Times contends that, “Some states may be misusing Obamacare grants in order to keep their state insurance exchanges operating—potentially flouting a provision in the law requiring them to cover the costs of the exchanges themselves starting this year.”

In fact, the ACA provided about $4.8 billion in grants to help states build and promote their Exchanges. As the article explains, before this year, states could use the grant money on overhead costs. However, a new provision that went into effect in January 2015 says that states can’t use the grants on maintenance and staffing costs; grant money must be spent on design, development and implementation costs.

The Fiscal Times spotlights California as a prime example of why state Exchanges are in troubled waters:

One of the worst examples comes from California, where the state’s exchange has been touted the most successful in the country for enrolling thousands of people. Covered California has already used up about $1.1 billion in federal funding to get its exchange up and running and is now expected to run a nearly $80 million deficit by the end of the year, according to the Orange County Register. The state has already set aside about $200 million to cover that, but the long-term sustainability of the program is very much in question.

In addition, state Exchanges like Hawaii might have to switch to the federal Exchange, Healthcare.gov, because of on-going financial solvency issues. “This is a contingency that is being imposed on any state-based exchange that doesn’t have a funded sustainability plan in play,” said Jeff Kissel, CEO of the Hawaii Health Connector.

According to the Post, states with the lowest enrollment are facing the biggest financial problems:

Turning operations over to the federal Exchange seems to be a popular alternative, but it doesn’t come without a cost: $10 million per Exchange, to be exact.

Although there are many options for state Exchanges to consider, it is likely that they will hold off on any final decisions until after the Supreme Court decides King v. Burwell. In this case, the Chief Justices will make a ruling in June that could either send a lifeline to ACA or remove a fundamental pillar of the law by under-cutting its ability to extend health insurance coverage to millions of Americans through its subsidy program.

The appellants in the King v. Burwell case say that IRS rule conflicts with the statutory language set forth in the ACA, which limits subsidy payments to individuals or families that enroll in the state-based Exchanges only. If the Court relies on a literal interpretation of the ACA’s language, millions of Americans who live in more than half of the states where the federal Exchange operates will not receive subsidies, thus undoing a fundamental pillar of the law. (Read more about the court case here.)

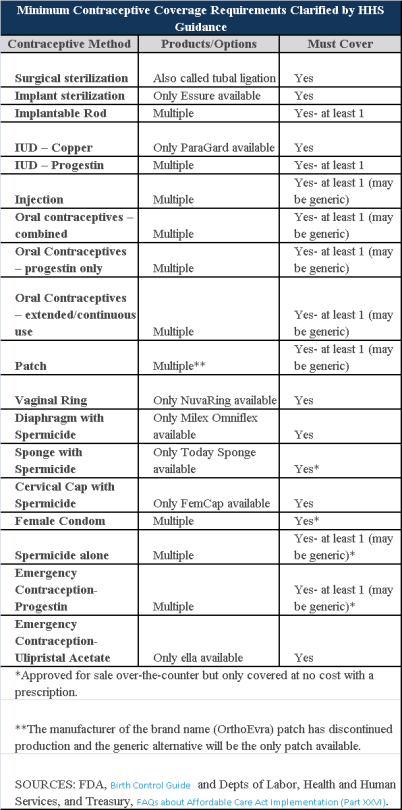

Plans and insurers must cover all 18 contraception methods approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, according to a new set of questions and answers on the Affordable Care Act’s preventive care coverage requirements.

“Reasonable medical management” still may be used to steer members to specific products within those methods of contraception. A plan or insurer may impose cost-sharing on non-preferred items within a given method, as long as at least one form of contraception in each method is covered without cost-sharing.

However, an individual’s physician must be allowed to override the plan’s drug management techniques if the physician finds it medically necessary to cover without cost-sharing an item that a given plan or insurer has classified as non-preferred, according to one of the frequently asked questions from the U.S. Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services and the Treasury.

The ACA mandated all plans and insurers to cover preventive care items, as defined by the Public Health Service Act, without cost-sharing. Eighteen forms of female contraception are included under the preventive care list. The individual FAQs on contraception clarified the following requirements.

The FAQ comes just weeks after reports and news coverage detailed health plan violations of the women coverage provisions of the ACA.

Testing and Dependent Care Answers

In questions separate from contraception, plans and insurers were told they must cover breast cancer susceptibility (BRCA-1 or BRCA-2) testing without cost-sharing. The test identifies whether the woman has genetic mutations that make her more susceptible to BRCA-related breast cancer.

Another question stated that if colonoscopies are performed as preventive screening without cost-sharing, then plans could not impose cost-sharing on the anesthesia component of that service.

The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) recently issued proposed new rules clarifying its stance on the interplay between the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and employer wellness programs. Officially called a “notice of proposed rulemaking” or NPRM, the new rules propose changes to the text of the EEOC’s ADA regulations and to the interpretive guidance explaining them.

If adopted, the NPRM will provide employers guidance on how they can use financial incentives or penalties to encourage employees to participate in wellness programs without violating the ADA, even if the programs include disability-related inquiries or medical examinations. This should be welcome news for employers, having spent nearly the past six years in limbo as a result of the EEOC’s virtual radio silence on this question.

A Brief History: How

Did We Get Here?

In 1990, the ADA was enacted to protect individuals with ADA-qualifying

disabilities from discrimination in the workplace. Under the ADA,

employers may conduct medical examinations and obtain medical histories as part

of their wellness programs so long as employee participation in them is

voluntary. The EEOC confirmed in 2000 that it considers a wellness

program voluntary, and therefore legal, where employees are neither required to

participate in it nor penalized for non-participation.

Then, in 2006, regulations were issued that exempted wellness programs from the nondiscrimination requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) so long as they met certain requirements. These regulations also authorized employers for the first time to offer financial incentives of up to 20% of the cost of coverage to employees to encourage them to participate in wellness programs.

But between 2006 and 2009 the EEOC waffled on the legality of these financial incentives, stating that “the HIPAA rule is appropriate because the ADA lacks specific standards on financial incentives” in one instance, and that the EEOC was “continuing to examine what level, if any, of financial inducement to participate in a wellness program would be permissible under the ADA” in another.

Shortly thereafter, the 2010 enactment of President Obama’s Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), which regulates corporate wellness programs, appeared to put this debate to rest. The ACA authorized employers to offer certain types of financial incentives to employees so long as the incentives did not exceed 30% of the cost of coverage to employees.

But in the years following the ACA’s enactment, the EEOC restated that it had not in fact taken any position on the legality of financial incentives. In the wake of this pronouncement, employers were left understandably confused and uncertain. To alleviate these sentiments, several federal agencies banded together and jointly issued regulations that authorized employers to reward employees for participating in wellness programs, including programs that involved medical examinations or questionnaires. These regulations also confirmed the previously set 30%–of-coverage ceiling and even provided for incentives of up to 50%of coverage for programs related to preventing or reducing the use of tobacco products.

After remaining silent about employer wellness programs for nearly five years, in August 2014, the EEOC awoke from its slumber and filed its very first lawsuit targeting wellness programs, EEOC v. Orion Energy Systems, alleging that they violate the ADA. In the following months, it filed similar suits against Flambeau, Inc., and Honeywell International, Inc. In EEOC v. Honeywell International, Inc., the EEOC took probably its most alarming position on the subject to date, asserting that a wellness program violates the ADA even if it fully complies with the ACA.

What’s In The NPRM?

According to EEOC Chair Jenny Yang, the purpose of the EEOC’s NPRM is to

reconcile HIPAA’s authorization of financial incentives to encourage

participation in wellness programs with the ADA’s requirement that medical

examinations and inquiries that are part of them be voluntary. To that

end, the NPRM explains:

Each of these parts of the NPRM is briefly discussed below.

What is an employee

wellness program?

In general, the term “wellness program” refers to a program or activity offered

by an employer to encourage its employees to improve their health and to reduce

overall health care costs. For instance, one program might encourage

employees to engage in healthier lifestyles, such as exercising daily, making

healthier diet choices, or quitting smoking. Another might obtain medical

information from them by asking them to complete health risk assessments or

undergo a screening for risk factors.

The NPRM defines wellness programs as programs that are reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease. To meet this standard, programs must have a reasonable chance of improving the health of, or preventing disease in, its participating employees. The programs also must not be overly burdensome, a pretext for violating anti-discrimination laws, or highly suspect in the method chosen to promote health or prevent disease.

How is voluntary

defined?

The NPRM contains several requirements that must be met in order for

participation in wellness programs to be voluntary. Specifically,

employers may not:

Additionally, for wellness programs that are part of a group health plan, employers must provide a notice to employees clearly explaining what medical information will be obtained, how it will be used, who will receive it, restrictions on its disclosure, and the protections in place to prevent its improper disclosure.

What incentives may

you offer?

The NPRM clarifies that the offer of limited incentives is permitted and will

not render wellness programs involuntary. Under the NPRM, the maximum

allowable incentive employers can offer employees for participation in a

wellness program or for achieving certain health results is 30% of the total

cost of coverage to employees who participate in it. The total cost of

coverage is the amount that the employer and the employee pay, not just the

employee’s share of the cost. The maximum allowable penalty employers may

impose on employees who do not participate in the wellness program is the

same.

What about

confidentiality?

The NPRM does not change any of the exceptions to the confidentiality

provisions in the EEOC’s existing ADA regulations. It does, however, add

a new subsection that explains that employers may only receive information

collected by wellness programs in aggregate form that does not disclose, and is

not likely to disclose, the identity of the employees participating in it,

except as may be necessary to administer the plan.

Additionally, for a wellness program that is part of a group health plan, the health information that identifies an individual is “protected health information” and therefore subject to HIPAA. HIPAA mandates that employers maintain certain safeguards to protect the privacy of such personal health information and limits the uses and disclosure of it.

Keep in mind that the NPRM revisions discussed above only clarify the EEOC’s stance regarding how employers can use financial incentives to encourage their employees to participate in employer wellness programs without violating the ADA. It does not relieve employers of their obligation to ensure that their wellness programs comply with other anti-discrimination laws as well.

Is This The Law?

The NPRM is just a notice that alerts the public that the EEOC intends to

revise its ADA regulations and interpretive guidance as they relate to employer

wellness programs. It is also an open invitation for comments regarding

the proposed revisions. Anyone who would like to comment on the NPRM must

do so by June 19, 2015. After that, the EEOC will evaluate all of the

comments that it receives and may make revisions to the NPRM in response to

them. The EEOC then votes on a final rule, and once it is approved, it

will be published in the Federal Register.

Since the NPRM is just a proposed rule, you do not have to comply with it just yet. But our advice is that you bring your wellness program into compliance with the NPRM for a few reasons. For one, it is very unlikely that the EEOC, or a court, would fault you for complying with the NPRM until the final rule is published. Additionally, many of the requirements that are set forth in the NPRM are already required under currently existing law. Thus, while waiting for the EEOC to issue its final rule, in the very least, you should make sure that you do not:

In addition you should provide reasonable accommodations to employees with disabilities to enable them to participate in wellness programs and obtain any incentives offered (e.g., if an employer has a deaf employee and attending a diet and exercise class is part of its wellness program, then the employer should provide a sign language interpreter to enable the deaf employee to participate in the class); and ensure that any medical information is maintained in a confidential manner.

Wondering what your employee is smoking in the break room, likely in violation of your “no-smoking” policy? Chances are it is an electronic smoking device, such as an e-cigarette or vaporizer. What should you do about it? Anything?

Many people are familiar with the increasingly popular e-cigarettes and vaporizers, forcing employers to now grapple with the question of whether to permit these devices in the workplace. The answer to this question is constantly changing based on new and revised laws and regulations. It can be difficult to stay aware of this ever-changing issue.

Not A Fad

Electronic smoking devices, particularly vaporizers, are skyrocketing in

popularity. One example of this continued popularity is shown by Oxford

Dictionary’s selection of the word “vape” as the 2014 word of the year. With

around five million Americans currently “vaping” and a $2.5 billion industry

with a 23% rise in sales in 2014, the electronic smoking industry is here to

stay.

There is no indication that growth will slow down any time soon, as sales are projected to surpass $3.5 billion this year and are leaving companies scrambling to meet rising demand.

How They Work

At a basic level, e-cigarettes and vaporizers allow users to consume nicotine

or other substances without smoking tobacco. However, there are noted

differences between e-cigarettes and vaporizers. E-cigarettes are smaller

cigarette-like electronic devices with batteries that heat a cartridge

containing liquid nicotine until it produces an inhalable vapor.

A vaporizer is comparatively larger than an e-cigarette and resembles a large pen. The vaporizer gradually heat the “e-liquid” with warm air, so it tends to last longer than e-cigarettes. Also, the vaporizer is refillable whereas an e-cigarette cartridge must be replaced when spent. To distinguish electronic vapor from smoke, users have coined the term “vaping,” instead of smoking.

The cartridges and refillable liquids contain mostly liquid nicotine and flavoring. However, there are also small amounts of propylene glycol or vegetable glycerin. The e-liquids also come in a wide assortment of flavors, including traditional tobacco as well as kid-friendly ones like gummy bear, snickerdoodle and watermelon mint.

The Controversy.

So what is all the fuss over these devices? To put it simply, there is not a

lot of established data about the health risks. The technology is new, as the

first e-cigarette was marketed in 2002. Manufacturers only introduced

e-cigarettes to the United States in 2007.

Since the products are new, it is not surprising that scientific data is limited. Scientific studies generally conclude that e-cigarettes and vaporizers are less harmful to an individual’s health than traditional tobacco cigarettes. The problem is that no one knows exactly what “less harmful” means.

Due to these uncertainties, there is significant controversy surrounding these devices. Advocates emphasize the value of e-cigarettes and vaporizers as an effective cessation device. Opponents point to the potential health risks. Studies have found that e-cigarette vapor may contain metal particles, carcinogens like formaldehyde, and enough nicotine to cause measurable secondhand exposure. But the long-term effects of e-cigarette vapor and direct exposure to liquid nicotine are unknown.

Federal And State

Prohibitions.

State and local governments were among the first to take action against

e-cigarettes and vaporizers. New Jersey, Utah, and North Dakota placed bans on

the use of the devices in public places and hundreds of cities have followed

suit. For example, Los Angeles, New York, Boston, and Chicago all banned the

use of e-cigarettes in restaurants, bars, nightclubs, and other public spaces.

Several California cities even require vendors to acquire special licenses to

sell e-cigarettes.

The federal government is now weighing in on the debate. The FDA wants to keep a closer eye on e-cigarette manufacturers. The agency is concerned that manufacturers are not required to comply with cleanliness or safety standards. Manufacturers are also currently under no obligation to disclose ingredients. In 2014, the FDA released proposed regulations that would deem tobacco products, including electronic smoking devices, subject to the federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.

The proposed rule received more than 82,000 comments during the notice and comment period which ended in August of last year, which likely means that it could be some time before the final rules are released. If approved, it would give the FDA the authority to set age restrictions and the power to partake in rigorous scientific review to monitor the ingredients, manufacturing process, and therapeutic claims of e-cigarette companies.

The Pros And Cons

Why is this relevant to you?

Employers must take action and determine their company’s stance on the issue before a supervisor walks into the break room to find the crew puffing on e-cigarettes. While the debate between opposition groups and advocates is just heating up, don’t wait to act. Weigh the pros and cons of allowing electronic smoking devices in the workplace and determine what is best for your company.

There are many factors that employers must take into consideration. Rightly or wrongly, e-cigarettes are perceived as tobacco. The Surgeon General’s office categorizes e-cigarettes as a “tobacco product.” Many state and local governments restrict e-cigarette usage in the same way as tobacco. Some insurance companies already impose a surcharge on e-cigarette users’ premiums, equating e-cigarettes to tobacco.

Employers with nicotine-free hiring policies, particularly those in the healthcare industry, have started to specifically ban e-cigarette users. As a result, these employers are treating users of e-cigarettes and vaporizers the same as users of traditional tobacco products.

Give serious consideration to whether allowing e-cigarette use in your workplace undermines a smoke-free environment. Allowing this practice is likely to cause distractions, may cause questions or concern from customers, and may anger other employees concerned about the secondary impact on their health.

Although the long-term effects of e-cigarettes and vaporizers are currently unknown, the developing consensus is that secondhand vapor contains nicotine or something worse. As a result, secondhand vapor may pose a risk to pregnant women, the elderly, children, and individuals with asthmatic conditions particularly.

Our Advice

We think that the cautious course of action is to treat electronic smoking

devices the same as traditional cigarettes and other tobacco products under

your no-smoking policy. Taking this step and eliminating the risk is simple:

simply amend your employee handbook to include electronic smoking devices,

e-cigarettes, and vaporizers, in the definition of smoking. Employees will then

have to use e-cigarettes outside or offsite, depending on your particular

policy.

By amending your employee handbook, you reduce risk and eliminate distracting behavior. Nonsmoking employees (almost always the majority) will feel comfortable at work and employees who smoke will only be required to comply with an already familiar procedure. Most importantly, employees will not have to worry about the potential harm caused by e-cigarette use or secondhand vapor.

Although amending the handbook may be the easiest answer, remember to follow the proper procedures when amending your handbook. Ensure that any amendments are in compliance with state law, federal law, and especially the National Labor Relations Act. Finally, ensure that all employees receive a copy of the updated handbook, understand the revisions, and acknowledge in writing that they understand the revisions.

The IRS released the 2016 cost-of-living adjustment amounts for health savings accounts (HSAs). Adjustments have been made to the HSA contribution limit for individuals with family high deductible health plan (HDHP) coverage and to some of the deductible and out-of-pocket limitations for HSA-compatible HDHPs.

The HSA contribution limit for an individual with self-only HDHP coverage remains at $3,350 for 2016. The 2016 contribution limit for an individual with family coverage is increased to $6,750. These limits do not include the additional annual $1,000 catch-up contribution amount for individuals age 55 and older, which is not subject to cost-of-living adjustments.

HSA-compatible HDHPs are defined by certain minimum deductible amounts and maximum out-of-pocket expense amounts. For HDHP self-only coverage, the minimum deductible amount is unchanged for 2016 and cannot be less than $1,300. The 2016 maximum out-of-pocket expense amount for self-only coverage is increased to $6,550. For 2016 family coverage, the minimum deductible amount is unchanged at $2,600 and the out-of-expense amount increases to $13,100.